When I speak of time, I’m referring to the fourth dimension.

Introduction

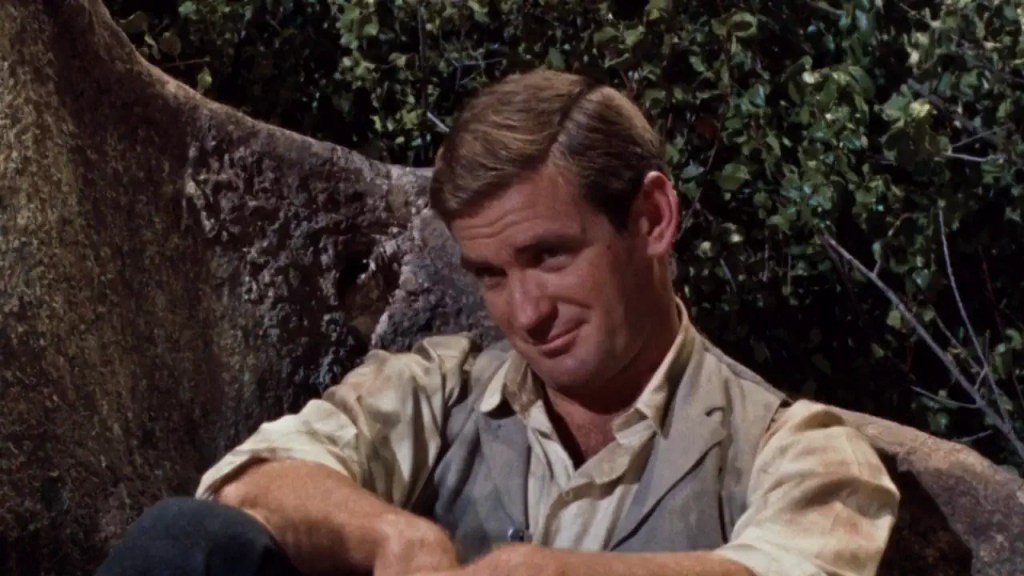

“The Time Machine” (1960) is George Pal’s elegant, effects-laden and deeply nostalgic adaptation of H. G. Wells‘ classic time travel novel, starring Rod Taylor, Yvette Mimieux and Alan Young. The film captivates not only with its carefully composed images and loving production design, but also with its special blend of adventure, romance and quiet melancholy. It became famous above all for its visionary depiction of a distant future that seems both hopeful and eerie. The film won the Oscar for Best Special Effects (now Visual Effects) for its technical time-lapse sequence, in which the seasons fly by and the world changes before the viewer’s eyes. It is still considered a milestone of classic studio cinema and a work that embodies the charm of practical effects and handmade film art in a special way.

Plot

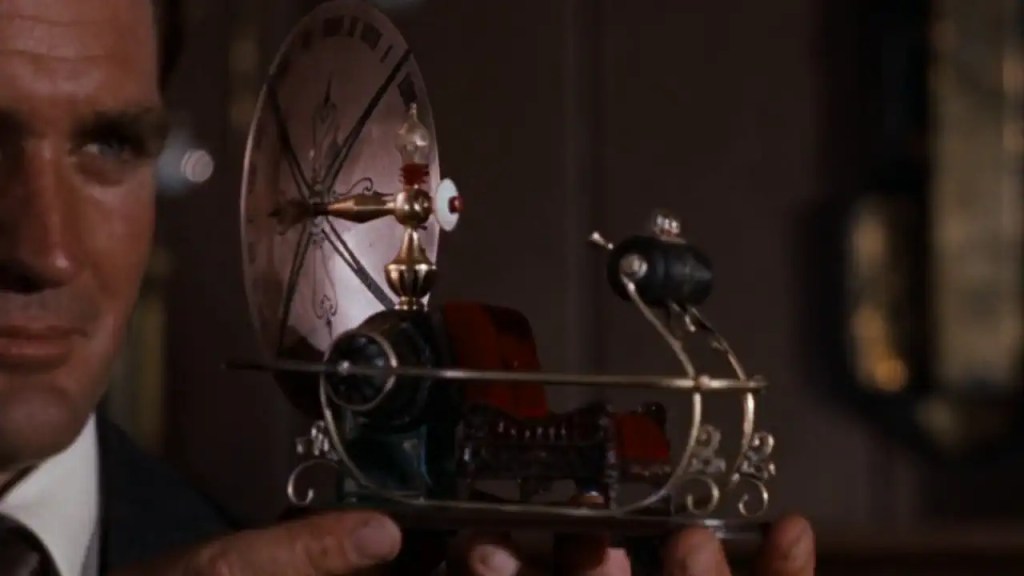

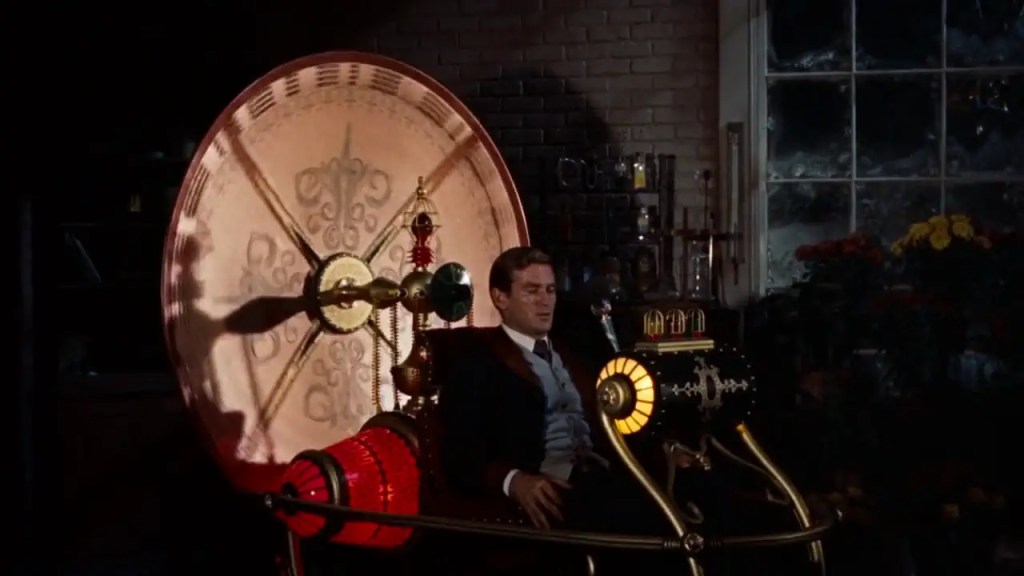

London around 1900: Inventor George invites a small group of wealthy friends to his magnificently furnished home to present one of his latest and most daring inventions – a working model of a time machine, which he demonstrates with a proud smile. While the guests waver between polite skepticism, incredulous amazement, and a touch of amused politeness, George reveals with a hint of secrecy that he has already built a full-size device. As soon as his friends have left, he takes his seat, surrounded by levers, measuring scales and the large, gleaming parabolic screen, and begins his journey through time.

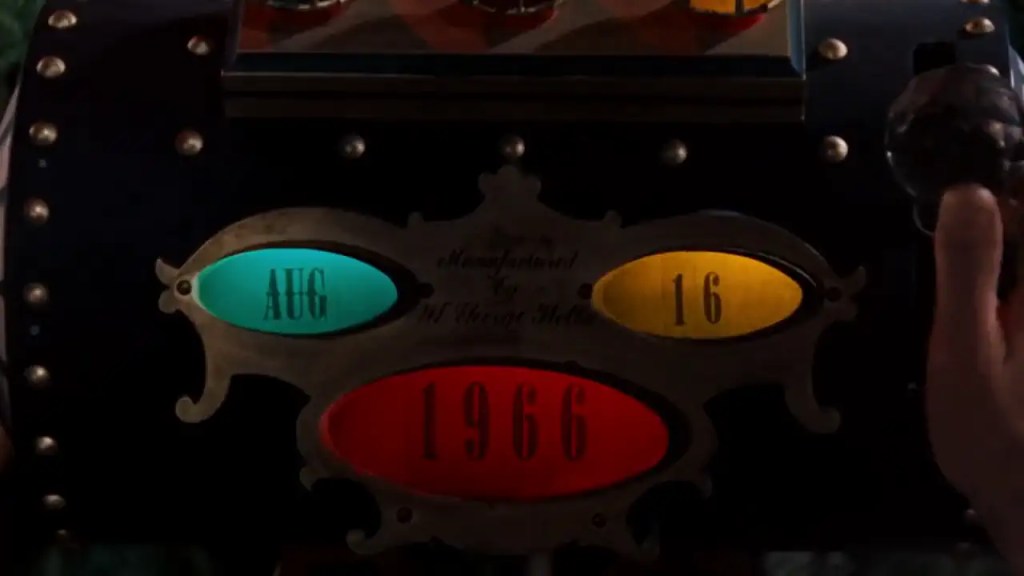

In a series of rapid, sometimes risky stops, he first lands in 1917, where he encounters an old friend in uniform in the midst of the First World War and experiences the oppressive atmosphere of a world shaken by war. Further leaps take him to London in 1940, scarred by nightly bombings and firestorms, and finally to 1966, which is plunged into chaos by a nuclear attack – an apocalyptic scenario in which burning debris rains from the sky and sirens wail in the distance. These visions of humanity’s self-destruction shake George to his core and drive him to flee further into the future until he ends up in the year 802,701.

There he encounters the childlike and apathetic Eloi, a superficially peaceful but frighteningly indifferent society living in a deceptive idyll. He soon discovers the gruesome secret: the Eloi are bred like cattle by the Morlocks, who live underground, to serve as food. George develops a tender bond with the young Eloi woman Weena, which motivates him to venture into the dark, mechanically rumbling realm of the Morlocks. There, with the help of fire and cunning, he sparks a rebellion, frees numerous captive Eloi, and leads them to the light of day. Exhausted, pensive, and with a changed view of humanity, he finally returns to 1900—only to board the machine again shortly thereafter. The final scene suggests with poetic openness that he has returned to the distant future, determined to continue his life there, “with all the time in the world.”

The Machine

The time machine itself is one of the most legendary props in film history and is considered an iconic example of successful film design. It was designed by MGM art director William (Bill) Ferrari, who masterfully combined Victorian elegance with visionary, futuristic elements. The curved wooden frames, polished brass, and velvety upholstery anchor the design firmly in the 19th century, while the imposing rotating parabolic screen and organically curved lines offer a glimpse into a technologically superior future. The vehicle was built by effects specialist Wah Chang, who not only worked with precision craftsmanship, but also ensured impressive stability and attention to detail, so that the machine appears both robust and luxurious on screen. The large rotating parabolic screen, curved leather seat, and brass-colored control levers gave the device an unmistakable silhouette that has been burned into the collective memory. A plaque on the control panel bears the tongue-in-cheek inscription “H. George Wells” – a direct homage to the author that connoisseurs will immediately spot. The original model later turned up in a collector’s hands, where it was treated like a treasure, and was lovingly restored in the 1970s by Bob Burns and colleagues, including a careful refurbishment of the paintwork, metal parts, and mechanics. Since then, it has been regularly featured in exhibitions, documentaries, and fan events, serving as a photo opportunity for science fiction fans from all over the world and becoming an enduring symbol of classic film science fiction.

Trivia

- The “lava” that engulfed London was actually a fermented oatmeal mixture that gave off a foul odor during filming—so intense that some crew members could only work nearby with their faces covered. Nevertheless, the viscous mass looked impressive on camera and gave the destruction scenes a surprisingly realistic texture.

- The “talking rings” in the museum, which serve as information storage devices in the future, are voiced by the unmistakable all-purpose voice of Paul Frees (uncredited), who was known for numerous animated films, amusement park attractions, and trailers. This detail escapes many viewers, but it brings a special smile to the faces of voiceover fans.

- In 1993, the short documentary/sequel miniature “Time Machine: The Journey Back” reunited parts of the original cast and offered not only nostalgic flashbacks, but also a short new scene that can be considered an unofficial sequel.

- Filming the Morlock scenes required elaborate makeup work, with actors sweating for hours under rubber and makeup to convincingly portray the nightmarish creatures.

- Rod Taylor insisted on performing some dangerous stunts himself, including the scenes in which he fights Morlocks – which resulted in minor injuries on set.

- For the time-lapse sequences showing the changing seasons, miniature models of buildings and plants were used, which were altered frame by frame to create the impression of accelerated time.

Book vs. film

Wells‘ novella (1895) tells the story of an unnamed “time traveler” who encounters the two species of Eloi and Morlocks in the year 802,701 – a distant future that has emerged from the deep-rooted class divisions of Victorian England. The Eloi represent a decadent, passive upper class, while the Morlocks are a sinister, exploitative working class living underground. The text takes the protagonist’s journey even further: he travels beyond the year of the Eloi into a dying, ghostly world under a blood-red glowing sun, where bizarre, crab-like creatures lurk sluggishly by a cooling sea – an image of the final extinction of all life. Weena’s fate remains far more tragic in the original than in the film, reinforcing the pessimistic tone. Pals‘ adaptation, on the other hand, personalizes and romanticizes: the hero is given the name George, which makes him more tangible to the audience. The original class allegory is expanded by a backstory that incorporates several world wars and ultimately a nuclear catastrophe, grounding the disaster not only in the hypothetical but also in the concrete and historical. Added to this is a visual motif that is missing from the book: the deafening air raid sirens, whose sound hypnotically drives the Eloi into the Morlocks‘ battle chambers. Overall, the tone of the adaptation veers more toward the adventurous and romantic, thereby softening the dark philosophical edge of the original.

Reviews at the time

Contemporary reactions were mixed, reflecting a certain uncertainty about how to classify the film in the context of its time. The New York Times praised the “polish and burnish” of the production, i.e. the high standard of craftsmanship and the care taken in the set design and cinematography, but criticized the dramaturgy, which at times seemed “creaky” and failed to maintain the tension promised by the subject matter. Variety praised the effects as “fascinating” and saw Rod Taylor as a new leading man whose charisma complemented the technical brilliance. Nevertheless, the paper criticized a noticeable lull in the pace of the futuristic act, which interrupted the narrative flow. The Washington Post’s response was generally positive, highlighting the strong special effects and the likable, accessible presence of the lead actor, who grounded the film in humanity. The New Yorker took a very different view, mocking the romance between George and Weena and the miniature worlds as naive and artificial. Overall, the picture that emerged was one of respect for the ideas, production design, and technology, combined with frowns over the tone, pace, and mixture of philosophical pretensions and adventure film elements.

Reputation today

Today, “The Time Machine” is considered a charming classic of studio trickery and a prime example of imaginative production design; the machine itself is often hailed as one of the great movie props and has become a symbol of the golden age of handmade science fiction cinema. The film appears in numerous “best of” lists for the genre and is often analyzed in film seminars as an example of imaginative set design and innovative special effects. On Rotten Tomatoes, the film currently has a 76% approval rating from critics, and on Metacritic it has a score of 67/100 (“generally favorable”), reflecting its enduring appreciation among critics and audiences alike. High-quality restorations and a Blu-ray release that was enthusiastically received by fans keep the title present in the circle of sci-fi canon works. The film also appears regularly at conventions, in retrospectives, and in tributes to classic effects, opening it up to a new generation of viewers who appreciate its blend of naive charm and visionary design.

Conclusion

George Pal’s “The Time Machine” is less a strict Wells exegesis than a poetic machine fantasy that feels like a cinematic invitation to dream: technically inventive, thematically accessible, and always tinged with a subtle touch of melancholy.

The mixture of adventurousness, romantic melancholy, and imaginative design makes it a work that appeals not only to genre fans but also to lovers of classic cinema. Those who love classic studio magic, matte paintings, handmade effects, and the charm of analog animation will find a journey through time that, despite its patinated naivety, works surprisingly well. The filmic machine is not only a narrative tool, but also a symbol of humanity’s longing to see beyond boundaries and explore new things. It is still running after more than six decades, and perhaps it is precisely this mixture of technical sophistication, narrative heart, and timeless design that ensures it will not fade from memory.

More

Trailer

External links

Keywords The Time Machine 1960 film analysis, George Pal Time Machine review, H. G. Wells Time Machine adaptation, Iconic movie props time machine design, Classic sci‑fi film special effects history, Time Machine oatmeal lava trivia, Eloi and Morlocks film vs. novella, Rod Taylor Time Machine stunts, Rotten Tomatoes score Time Machine 1960, Time Machine legacy and reputation today

Hashtag: #TheTimeMachine #GeorgePal #HGWells #ClassicSciFi #MovieProps #SpecialEffects #TimeTravel #FilmTrivia #EloiMorlocks #RetroCinema #SciFiMovie #IconicDesign #RodTaylor #SciFiClassic

Kommentar verfassen :