Look, up in the sky! It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s Superman!

Introduction

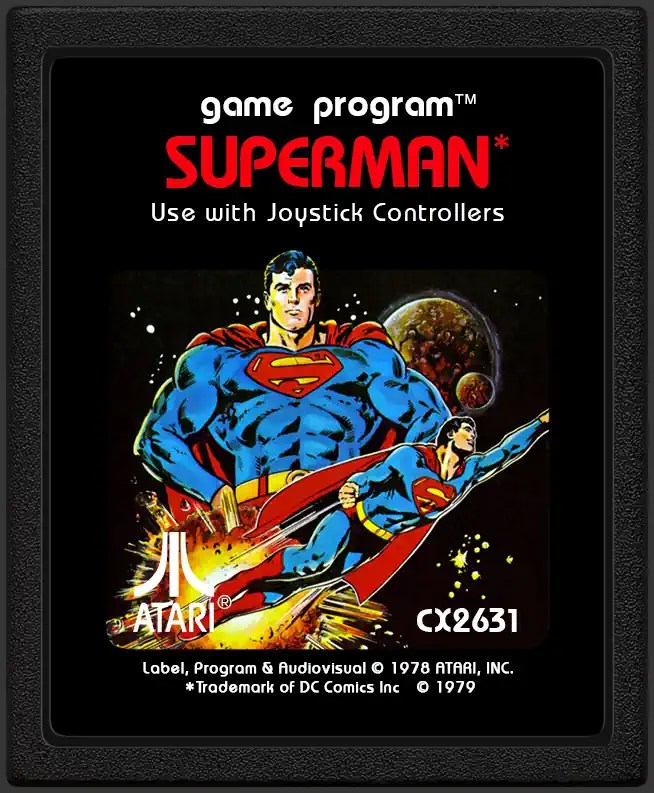

The Atari 2600 game “Superman” is one of the early attempts to transfer the popularity of major pop culture licenses to a home console format. At a time when many console titles were still heavily influenced by arcade thinking (short rounds, simple goals, immediate repetition), “Superman” made a somewhat bigger promise: a small, coherent game world in which players could orient themselves, pursue goals, and recognize the character as a “brand.”

At a time when game mechanics were still largely abstract and graphics could only convey limited detail, the game had to convey the Superman feeling through a few clear signals. These included, above all, freedom of movement, speed, and the iconic flying, which immediately created a different rhythm than in ground-based action games. The appeal lay in not simply controlling a generic avatar, but in portraying Superman – with his ability to fly, his super strength, and the typical switch between Clark Kent and hero – as a playful concept.

This role reversal in particular is more than just thematic decoration: it translates the character’s double life into a concrete game system and forces the player to rethink their approach depending on the situation. At the same time, the game shows how much productions at that time relied on instruction, imagination, and the willingness to read symbols as “city,” “danger,” or “task.” From today’s perspective, this seems cumbersome, but historically it is an interesting step toward license-based games that not only bear a name but actually transform character traits into mechanics.

Gameplay

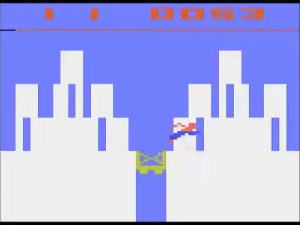

In terms of gameplay, “Superman” is designed as a mixture of action and light exploration. The goal is usually to overcome a threat that spans several screens, forcing the player to plan routes, memorize landmarks, and regularly commute between locations. The game uses the classic Atari 2600 principle of a world consisting of a series of screens that can be turned like pages: as soon as you reach the edge of a screen, the view “jumps” to the next area. On the one hand, this technique creates a sense of map and context, but on the other hand, it also brings with it typical Atari idiosyncrasies, such as abrupt transitions that require precise control.

You move through a map (city areas and surroundings), search for relevant locations, and interact with enemies or events. The core consists less of a linear course and more of a repeated alternation between exploration, finding triggers, and then working through the respective situation. This leads to a kind of “detective work” within the scope of what was possible at the time: you learn which screens represent what, which symbols stand for danger or progress, and when it makes sense to cut a route instead of taking a detour.

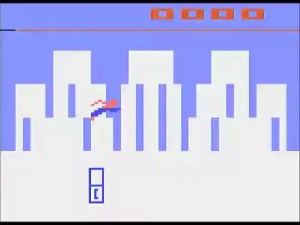

A central element is the ability to fly, which significantly speeds up navigation and gives the game a unique selling point compared to many contemporary titles. Flying acts as a tool for increasing efficiency: you can quickly cover distances, react faster, and actively determine the pace of the game. At the same time, this creates a contrast between “rough” movement across the map and the moments when you have to reposition yourself more precisely for an interaction or an obstacle – a tension that is very typical of early console games.

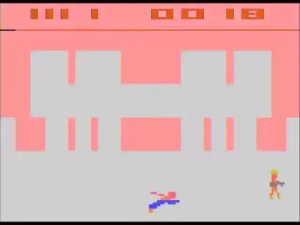

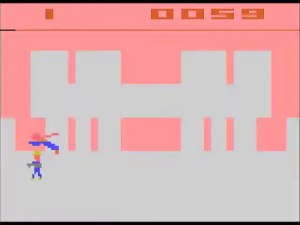

In addition, the switch between Clark Kent and Superman is significant in terms of game mechanics: it is not just a thematic accessory, but part of the solution, for example to overcome certain situations or control the flow of the game. The role change thus functions as a deliberate tempo module and as a design trick to translate the license idea (double life) into rules. Opponents and obstacles are to be understood more as functional symbols (typical for the era) than as visually detailed characters; this creates gameplay that relies heavily on understanding the rules, recognition, and “reading” the game world. Once you have internalized this symbolic language, the game feels less chaotic and more like a series of small tasks spread across a compact but coherent environment.

Technology

Technically, “Superman” operates within the narrow confines of the Atari 2600 hardware. The system was notoriously limited: very little RAM, simple sprites, severely restricted color and detail display, and image output that often had to be maximized with tricks (e.g., alternating sprite usage per scanline). In addition, the graphics logic was fundamentally “object-poor”: the console could only display a few moving elements at a time, which is why developers often had to work with reuse, time-delayed drawing, and occasional flickering to simulate a lively game world.

Accordingly, characters and objects are stylized, sometimes difficult to distinguish, and the world appears minimalistic from today’s perspective. What you see on the screen is less a detailed city than a symbolic representation that conveys meaning through colors, shapes, and recurring patterns. The controls and collision logic are also closely related to the technical constraints: precise movements and clean hit detection are possible on the 2600, but must be implemented sparingly because each additional rule and each additional state ties up resources.

It is interesting to note that “Superman” nevertheless depicts several states and mechanics that go beyond mere point collection: flight, role changes, a multi-part game world, and a mission-like goal system. This brings the game closer to a “system design” in which different modes (e.g., faster traversal in flight vs. situational action on the ground) interlock. This “complexity” is particularly remarkable for early 2600 titles because it increases the programming and design effort without being able to display it graphically in a lavish way. Much of what looks like “more game” is therefore created by rules, state changes, and the organization of the game spaces – not by additional visual assets.

The technical impression is therefore less “impressive” in a purely visual sense, but rather in the ambition to bring together many systems under strict limits. From today’s perspective, ‘Superman’ can also be read as an example of how early developers used the console as a real-time “bag of tricks”: they used timing, repetition, and clever simplification to achieve an effect that at least functionally fulfilled the promise of the license.

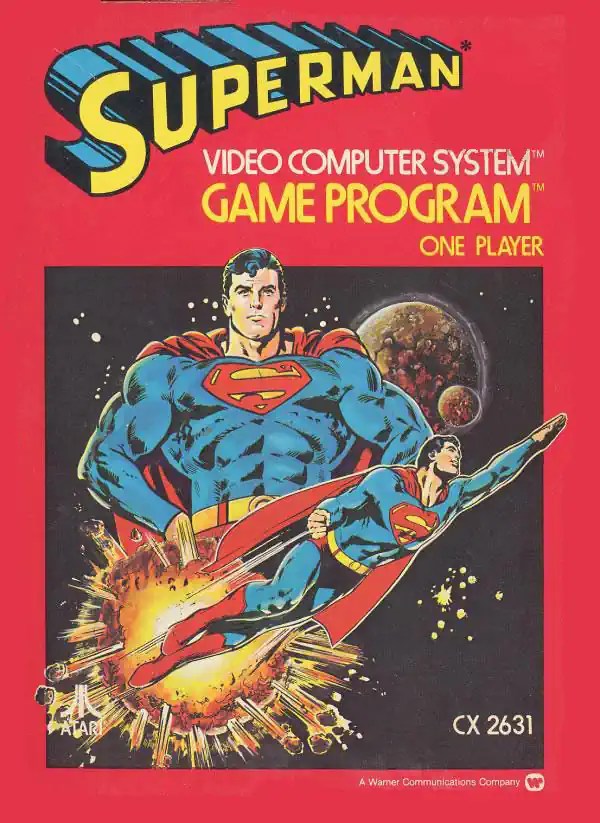

Trivial

As an early licensed game, “Superman” is also a testament to how quickly the gaming industry latched onto movie and comic book brands. In the Atari era, well-known names were an important selling point because the packaging, instructions, and brand logo often communicated more effectively than the actual on-screen action. Especially in retail stores, the box was often the most important “pitch”: the cover art and brand name conveyed a promise that the screen, with its symbolic graphics, could only deliver to a limited extent.

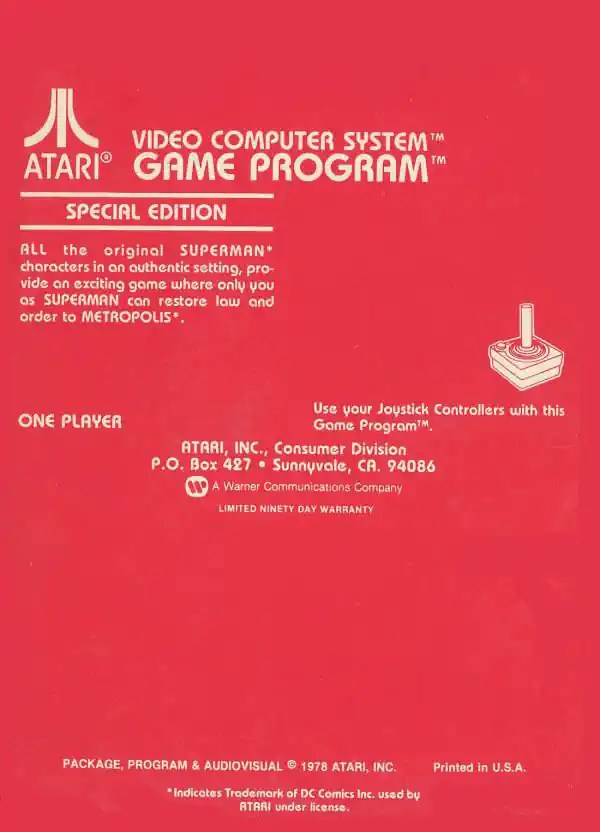

Many players learned game mechanics from the manual, not from in-game tutorials. The booklet not only explained buttons and objectives, but also provided context, terms, and meanings for symbols that could hardly be explained in the game itself. This created a special form of “co-authorship” between the product and the audience: Those who had read the manual interpreted screens, objects, and events in a much more targeted manner and found the game world more coherent.

“Superman” is thus exemplary of a time when the manual was practically part of the product and the player’s imagination filled in the gaps in the presentation: you “knew” that you were Superman – the game only had to hint at it. At the same time, this reveals an early area of tension in licensed games: the more the brand raises expectations of iconic locations, characters, and dramaturgy, the more noticeable technical shortcomings become. The fact that “Superman” still worked as an experience was precisely due to this media mix of packaging aesthetics, explanatory instructions, and the willingness to mentally “translate” what was depicted. In this respect, the title should be seen less as a curiosity and more as a typical example of how early home console games gained considerable significance and comprehensibility through paratext (box, manual, brand).

Criticism at the time

Contemporary reviews of such early console games often fluctuated between fascination and frustration. Typically, the license, the idea of flying, and the comparatively “adventurous” target structure were perceived positively in ‘Superman’ because they stood out from simple arcade conversions and created a stronger sense of “task” rather than mere point hunting. Many observers saw this as a pleasant change: not only did it require reflexes, but also a simple form of orientation and planning, which was not yet a given for home games at the time.

The readability of the game world was often criticized: those who did not understand exactly what a symbol meant, where to go, or why an event was triggered could find the game unclear or “random.” This criticism was closely related to the fact that the game conveys its information in a very indirect way. Without instructions or a longer “acclimatization period,” it was easy to miss targets, overlook important locations, or misinterpret the meaning of individual objects. As a result, for some players, the mission structure seemed more like a sequence of difficult-to-understand states than a clear task.

The controls and collision detection also seemed clunky to testers at the time – not unusual for the Atari 2600, but particularly noticeable in a superhero game because the fantasy promise (“Superman feels powerful”) was at odds with the technical reality. A hero who acts effortlessly in comics or movies suddenly collides with the edges of the screen in the game or has to be positioned very precisely to trigger an interaction. It was precisely this discrepancy between expectation and user experience that strongly influenced the overall impression.

Overall, it was often described as ambitious but not always elegantly implemented – a game that wants more than the platform can easily deliver. Those who embraced the symbolic language and the peculiarities of the controls were able to appreciate the approach as surprisingly “big” for its time; those who expected an immediate, clearly guided superhero fantasy, on the other hand, tended to get stuck on the limitations of the hardware and the cumbersome communication of the objectives.

Cultural influence

The cultural significance of “Superman” on the Atari 2600 lies less in the fact that it is still a dominant classic in terms of gameplay, but rather in the fact that it provides early blueprints for superhero adaptations in the video game sector. Precisely because the game attempts to be more than just a point-scoring exercise, it is often seen in retrospect as an early step towards “systemic” superhero games: not just reacting, but also navigating, prioritizing, and understanding a small world as a coherent space.

The idea of using abilities such as flying as a core mechanic and translating a role change (Clark Kent/Superman) into a playful system is conceptually interesting: it shows that developers tried very early on to treat a character’s attributes not just as decoration, but as mechanics. In doing so, the title touches on questions that would later become central to the genre, such as how “power” can be made playable without making the game too trivial, and how identity (hero vs. civilian) can be translated into rules, tempo, and risk.

In addition, “Superman” represents the early phase of licensed games, in which brand identity, packaging design, and expectation management played a central role. Especially with an icon like Superman, expectations from comics and movies immediately collide with the limitations of the hardware – a tension that has accompanied licensed games for decades. At the same time, these types of titles contributed to video games being perceived as part of the pop culture ecosystem: not isolated as a technological gimmick, but as another medium that can “interpret” well-known characters.

In retrospect, it is therefore a cultural artifact that reveals the dynamic between pop culture (comics/films) and the still young video game industry: experiments were conducted to see how icons could be translated into interaction – even if the result seems awkward from today’s perspective. In the retrogaming scene and in the historiography of the medium, “Superman” appears less as a perfect game and more as a reference point for early design ambitions, for the mechanization of character traits, and for the role of licenses as a catalyst to justify more complex game objectives and “world” concepts in the first place.

Conclusion

“Superman” for the Atari 2600 is a typical product of its time: technically limited, highly abstract in design, but with a palpable ambition. The game attempts more than many titles of the time by combining a small world, mission-like objectives, and character-specific abilities, thus taking a step away from purely reactive “screen games” toward a structure that is more strongly based on context. It is precisely this mixture that makes it historically interesting, because it shows how early on developers were already thinking about “world logic” and character abilities as the core of design – even if the presentation could only convey these ideas symbolically.

Anyone playing it today has to embrace the logic of early console games: symbols instead of details, manual knowledge instead of in-game explanations, and a high degree of interpretation. You have to be willing to accept transitions between screens as part of the system, to orient yourself through repetition, and to deduce the meaning of objects from a few visual clues. In this sense, the game is less an immediate action extravaganza than a small, rule-based exploration task that derives its effect from the interplay of map, tempo, and state changes.

It is rarely considered a milestone in terms of perfect playability; the controls, readability, and feedback are too heavily influenced by the limitations of the platform. However, it is remarkable as an early example of how superhero mechanics can be conceived: flying as a traversal tool, role-switching as a systemic trick, and the idea of a “mission” spread across multiple rooms point toward later superhero games that formulate precisely these elements with modern technology. Thus, “Superman” is remembered less for its polish than for its ambition and early design decisions.

Kommentar verfassen :