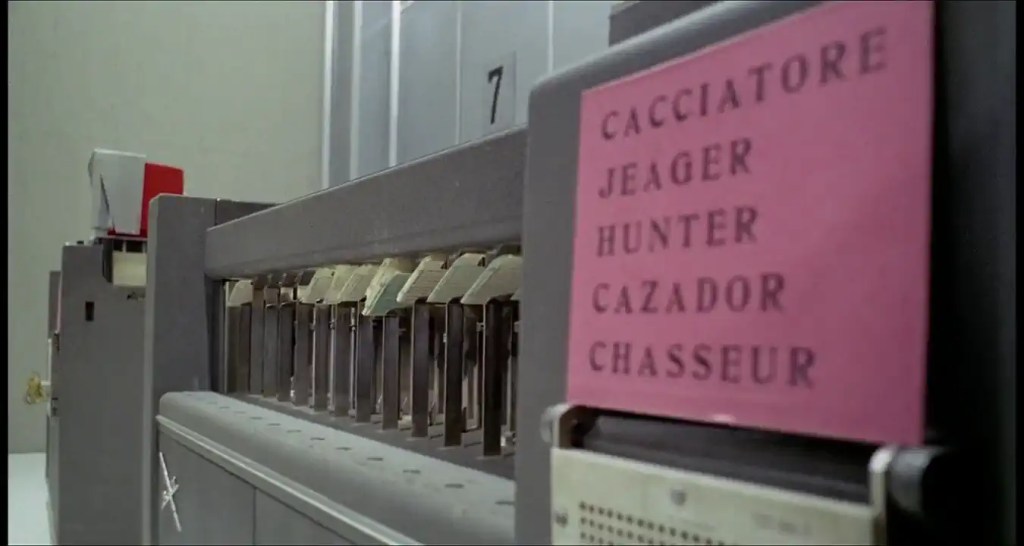

The rules of the Big Hunt are quite easy.

Rule 1: Each member is obliged to take ten hunts; five as a Hunter, five as a Victim, alternately.

Rule 2: The Hunter shall know all about his Victim – name, address… habits, too.

Rule 3: The Victim shall not be told who his Hunter is. He must find out… and kill him!

Rule 4: The winner of each separate Hunt will win money.

The one who comes out alive after the tenth Hunt… shall be proclaimed decathlete.

He shall receive honors… and ONE MILLION DOLLARS!

The Original Battle Royale

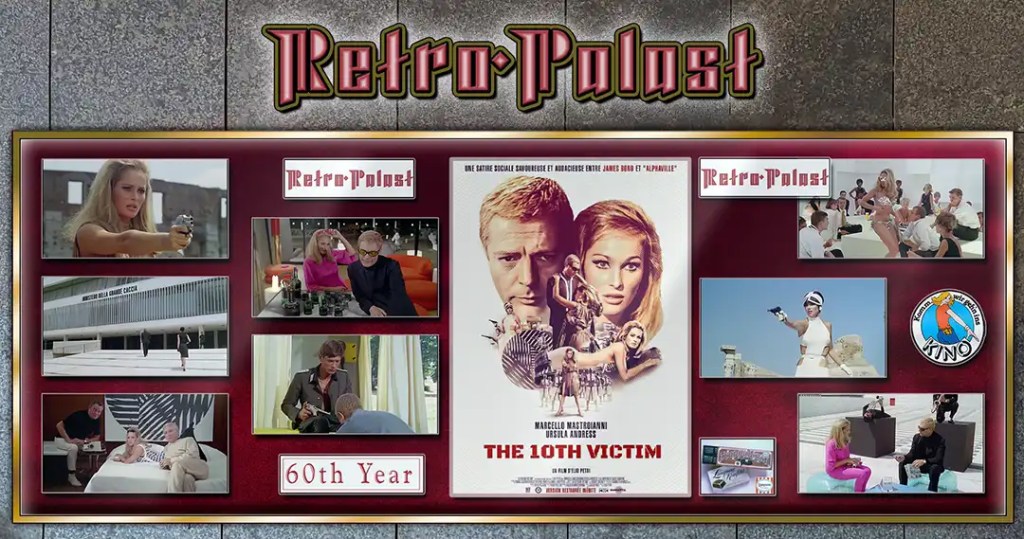

Before Battle Royale, The Hunger Games, or even The Purge took up the idea of state-sanctioned killing as entertainment, there was already The 10th Victim. The Italian science fiction film by Elio Petri from 1965 is considered a style-defining precursor to this subgenre and a pioneer in the cinematic exploration of the tension between media, violence, and society.

Based on a short story by Robert Sheckley, the film combines cold futuristic pessimism with pop art-style satire, garishly colorful fashion aesthetics, and a bitingly ironic view of consumerism, fame, and the spectacle of killing. This introduction could easily appear in a glossy magazine about modern dystopias, but the work was far ahead of its time.

Petri tackles topics that only became part of the cultural mainstream decades later: the commercialization of violence, manipulation by the mass media, and the audience’s voyeuristic desire to see others suffer. Even back then, the film reflected a world in which authenticity was replaced by performance and spectacle supplanted reality.

The 10th Victim is not purely a science fiction film, but rather a product of its time – a science fiction subgenre that is now referred to as Swingpunk – the Swinging Sixties, an era of experimentation in which the boundaries between high culture, pop culture, and politics became blurred. The film exudes the same energy as fashion photography from London or avant-garde art from Paris, with bold colors, exaggerated forms, and a dash of ironic futurism. Petri uses this cultural chaos as a stage for a grotesque farce about the human need for fame and recognition – whatever the cost. In doing so, he not only presents a picture of society, but also creates a hall of mirrors in which viewers recognize themselves as part of the spectacle. Every shot is carefully composed, every camera angle exaggerates the everyday into the surreal. This creates a fascinating tension between aesthetics and ethics, between a garish surface and a moral abyss. This ambivalence is the source of the film’s enduring fascination, which is far more than just a curiosity of the 1960s.

Plot

In the near future, humanity has channeled its warlike instincts into a legal game: “The Big Hunt,” a global competition in which hunters and the hunted are allowed to kill each other—in front of cameras, under the supervision of an all-powerful organization, and with lucrative sponsorship deals. Violence is not frowned upon here, but institutionalized—an outlet intended to secure peace. This concept is explained with frightening logic: instead of waging wars that destroy entire nations, bloodlust is channeled into a regulated competition that is also economically profitable. Cameras broadcast every shot, every movement; viewers bet on their favorites, and companies use the spectacle to advertise their products. Violence becomes routine, a lucrative industry in which moral questions no longer play a role.

Each participant must survive ten successful rounds – five as a hunter, five as a victim. Those who survive all of them become rich, famous, and celebrated as heroes by society. Death becomes entertainment, hunting a status symbol. This system not only creates stars, but entire careers – magazines report on the best killing techniques, fans collect autographs from survivors, and children grow up with the idea that one day they too will be able to participate. The game becomes a mirror of a society that has lost its moral compass.

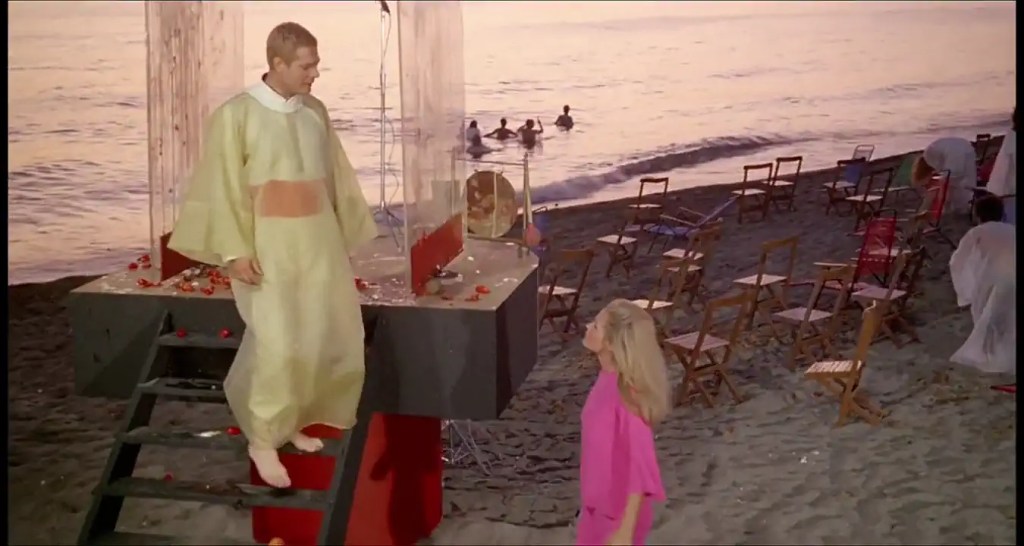

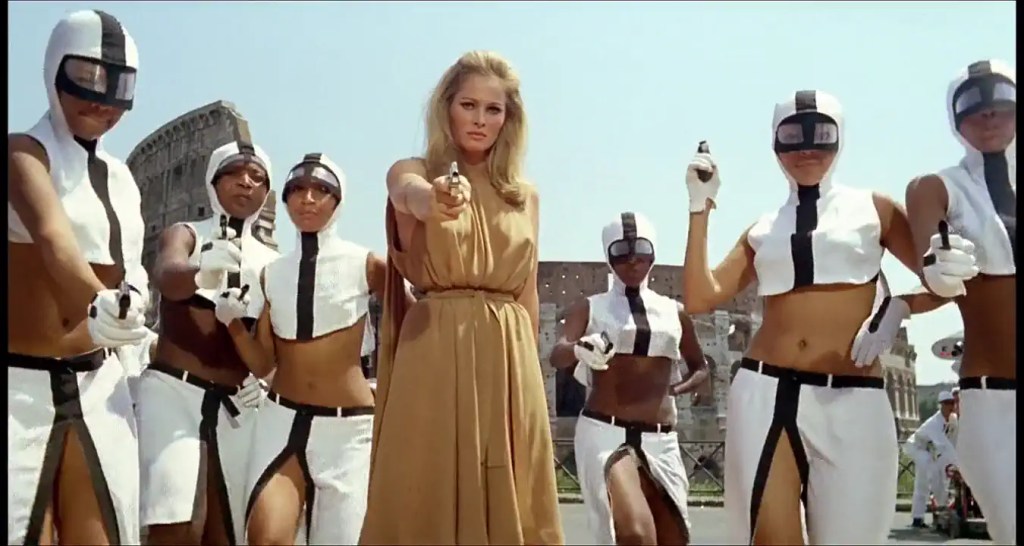

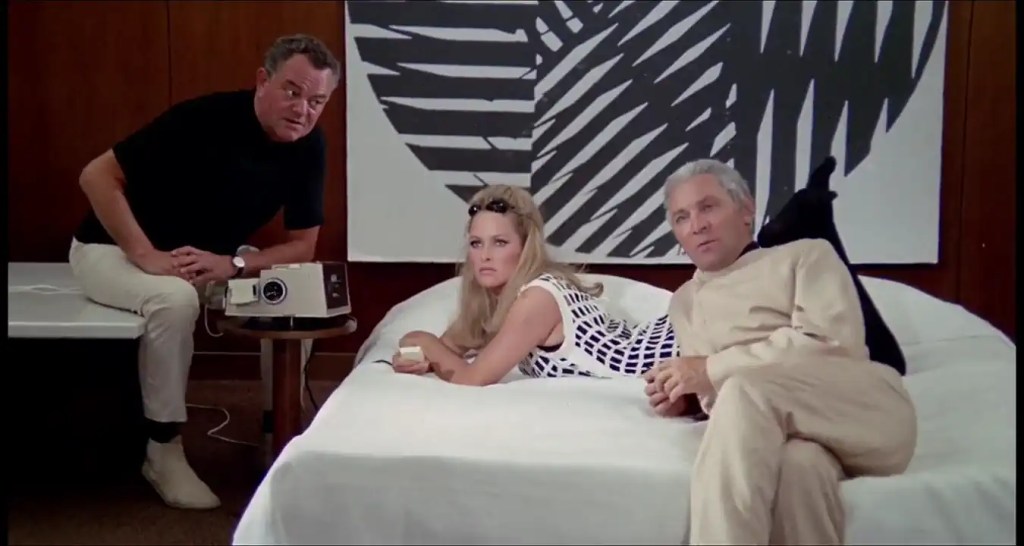

The plot follows Caroline Meredith (played by Ursula Andress), an American hunter who travels to Rome for her tenth and final “victim.” There she meets Marcello Poletti (Marcello Mastroianni), her designated opponent—charming, lethargic, in debt, and disappointed with life. What begins as a merciless game of cat and mouse increasingly turns into an absurd love game. While Caroline plans to stage her final kill in a live show, Marcello searches for a way to escape the deadly game – and perhaps still find love. A tension develops between the two, born of fascination, deception, and tenderness, which lends the film an unexpected depth. Petri uses their relationship to raise questions about authenticity, trust, and manipulation—in a world where even feelings have become commodities.

Petri stages the action with exaggerated artificiality, almost like a fashion campaign or commercial. Colors, costumes, and architecture scream for attention, while the characters appear like puppets amid this visual overload. Scenes abruptly shift from humorous lightness to cold brutality, causing the viewer to constantly oscillate between fascination and revulsion. The most famous scene: Caroline uses a gun built into her silver bra to shoot her victim – an image that is not only iconic but also bitterly ironic: beauty as a weapon, eroticism as marketing. This scene is symbolic of the entire work: a dance on the border between glamour and violence, between irony and tragedy, in which every pose is both satire and self-exposure.

Trivial

- Template: The film is based on Robert Sheckley’s short story “The Seventh Victim” (1953). Sheckley later even wrote a novel based on the film and further sequels, inspired by the cinematic version of his idea. It is particularly interesting that Sheckley himself was influenced by Petri in his later works – a rare feedback loop between author and director. His literary version of the film expands the philosophical dimension of the story by raising questions about identity, reality, and the meaning of competition.

- Filming: The film was shot in Rome, including iconic locations such as the Palace of Italian Civilization—a monument that perfectly embodies the aesthetics of power and modernity. Petri used post-war architecture as a reflection of a future in which individuality disappears behind concrete and glass. In addition to the official locations, the team also used improvised studios and experimental lighting techniques to enhance the futuristic look. The cinematography by Gianni Di Venanzo—one of Italy’s greatest cinematographers—gives the film its unmistakable elegance and depth.

- Music: The soundtrack by Piero Piccioni combines jazz, bossa nova, and electronic sounds. The main song, “Spiral Waltz,” is now considered a classic and, with its light, almost humorous tone, contributes to the contrast between style and content. Piccioni experimented with unusual instruments such as the theremin and harpsichord to give the film a playful and absurd soundscape. The music not only accompanies the action, but also comments on it ironically—a soundtrack that dances with the film rather than simply accompanying it.

- Influence: Numerous designers and filmmakers, from Quentin Tarantino to Nicolas Winding Refn, cite Petri and the visual language of this film as inspiration for their work. Pop artists such as Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein were also influenced by the aesthetics of the film posters. More recently, fashion houses such as Prada and Moschino have incorporated references to the film in their collections – proof that “The 10th Victim” has had an impact far beyond the boundaries of cinema. Critics see it as a work that captured the zeitgeist of the 1960s and at the same time wrote the visual code of the future.

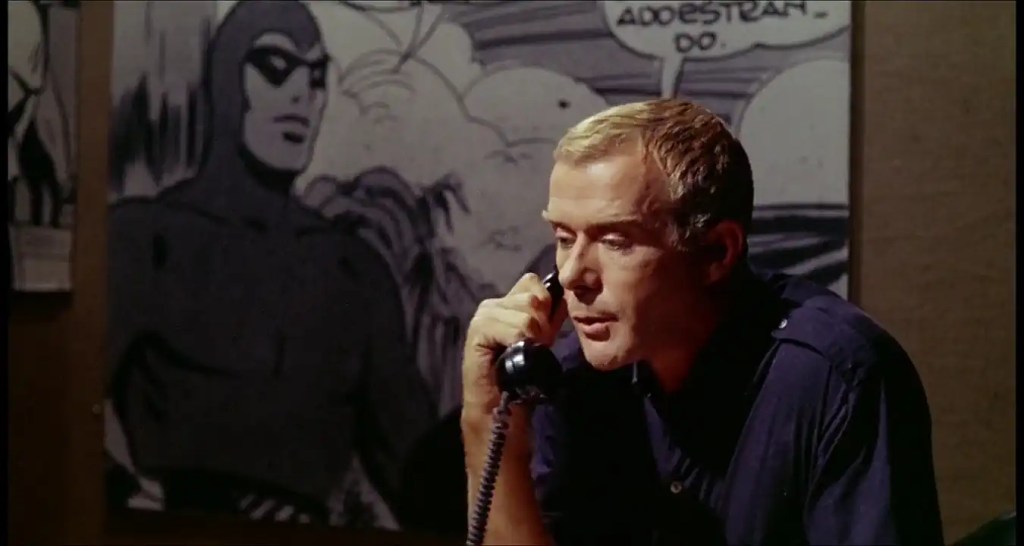

Actors

- Marcello Mastroianni – as Marcello Poletti: The Italian superstar plays against his usual image here. Instead of the virile charmer from Fellini’s films, he embodies a broken, cynical man – dyed blond, tired of life, but full of ironic elegance. His portrayal lends the character a subtle tragedy: behind the elegant surface shimmers an existential weariness, which Mastroianni nuances with minimal gestures and ironic smiles. Particularly remarkable is how his performance reveals the conflict between human warmth and social alienation – a theme that Petri repeatedly explores. Mastroianni’s Marcello seems like a man who has seen too much, a symbol of modern man breaking down under the weight of his own civilization.

- Ursula Andress – as Caroline Meredith: After her appearance as a Bond girl in Dr. No, Andress became an international style icon. In “The 10th Victim,” she is both ice-cold and seductive – a symbol of consumer society, in which even death becomes a show. Andress gives her character an almost mythological quality, a mixture of Aphrodite and Amazon, who loves the camera as much as she controls it. Her movements, her gestures, and her clothing are expressions of a power that is not physical but performative. Caroline Meredith is not a woman, she is a concept—beauty as the ultimate weapon.

- Elsa Martinelli – as Olga: a cynical friend of Mastroianni’s who comments on the game and acts as the voice of society. Martinelli plays this role with sophisticated ease; she is an observer, a mocker, and a commentator all at once. Her dialogues contain some of the film’s most biting lines and make it clear that Petri uses his supporting characters as moral sounding boards.

- Salvo Randone – as manager and organizer of the “Big Hunt”: He represents the bureaucratic apparatus behind the spectacle and symbolizes the alienation between man and morality. His stiff posture, bureaucratic language, and ironic pragmatism make him an early symbol of the technocratic cynicism that would later shape many dystopias.

Petri does not cast his stars at random – he uses their public images to deconstruct them. Mastroianni, the eternal lover, and Andress, the global sex symbol, become pawns in a cynical world where even love is a calculated maneuver. Their interaction is a game of glances, irony, and deception that addresses the ambivalence between passion and manipulation. Petri directs them like characters in a play that oscillates between comedy and tragedy, revealing a complex dynamic of desire, mistrust, and self-promotion.

Design and style

The design of The 10th Victim is a manifesto of European 1960s futurism – what is now referred to as Swingpunk – and one of the most important vehicles for its message. Fashion, architecture, props, and color design are not mere decoration, but actively contribute to the narrative. Petri and his set designers created a world in which aesthetics become a mirror of social superficiality. The geometric clarity of the buildings, the sterile white of the rooms, and the bright accent colors look like something out of a fashion magazine—and that is exactly the intention: this future is styled to the point of coldness.

Fashion plays a central role in this. Ursula Andress wears futuristic outfits made of metal, latex, and plastics reminiscent of Paco Rabanne or André Courrèges – designers who were experimenting with futuristic silhouettes at the time. Her costumes emphasize her function as an icon of the consumer world: glittering, aloof, perfectly staged. Mastroianni’s suits are also not chosen at random – they combine classic Italian elegance with technical austerity and reflect his position between humanity and machine.

The architecture, especially the shots in Rome’s EUR district, underscores this visual language. Clean lines, monumental structures, and open spaces convey an atmosphere of power and alienation. Combined with pop-art props—brightly colored furniture, abstract sculptures, billboards, and screens—this creates an aesthetic conflict between order and excess. This mixture of pop art, modernism, and satire makes the film a stylistic testimony to its time.

Petri himself understood design as an expression of a world in which form has become more important than content. His sets, costumes, and color concept speak the same language as his plot: beauty has become a weapon, style a system, and life itself a stage.

Critical reception at the time

Upon its release in 1965, “The 10th Victim” was a commercial success in Europe, particularly in Italy, France, and Germany. In the US, however, reception was divided. While European critics praised the film as funny, intelligent, and stylistically brilliant, many American reviewers found it “too European,” “too fashionable,” and “too aloof.” This transatlantic divide in perception remains interesting today, as it highlights how differently aesthetic and narrative codes are interpreted in different cultures: What was considered avant-garde in Europe often seemed too cool or intellectual to American audiences.

Contemporary voices described the film as “a garish fashion farce” (Variety) or “a stylish satire without an emotional core” (New York Times). Others praised its “glittering coldness” and its “humorously malicious view of the future.” In Italy, Petri was celebrated as one of the most important representatives of a new wave of political film—even before he gained international recognition with Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion. French critics in particular, including the editors of Cahiers du Cinéma, saw Petri as an heir to the Surrealists, who merged capitalism, advertising, and desire into an absurd circus of modernity. Some pointed out that “The 10th Victim” said more about Western society than many serious dramas of the time.

The film’s aesthetics were particularly highlighted: the play with colors, light, and architectural lines made “The 10th Victim” a visual experience that was ahead of its time. While Hollywood still relied on classic sets, Petri transformed the urban landscape of Rome into an abstract stage set of the future. Critics also emphasized the importance of fashion in the film—it functions not only as decoration, but as a social language, a visual manifesto of the 1960s. Some European film magazines even described the film as “fashion criticism in motion.” In addition, many reviewers compared Petri’s irony to Stanley Kubrick’s satirical tone in Dr. Strangelove, which had been released just a year earlier. These comparisons made it clear that Petri was not only an aesthete, but also a filmmaker with a sharp political and philosophical eye.

Reputation today

Today, The 10th Victim is considered a cult film and one of the first serious attempts to combine media criticism with science fiction and black humor. In academic analyses, it is described as an early example of what would later be called “media satire” or “reality dystopia.” However, its significance extends far beyond the genre: the film is now also interpreted as a sociological document that anticipates the dynamics of consumer society and self-expression decades before the Internet age. Numerous essays praise Petri for his ability to entertain and provoke viewers at the same time—a balance that later inspired many media critics.

Film historians see it as an aesthetic document of the 1960s, in which fashion, advertising, and violence merge into a pop-cultural collage. The film subtly addresses the question of how far people will go to be seen—a theme that seems more relevant than ever in the age of social media. Many scholars emphasize that Petri already anticipated the phenomenon of “self-marketing” here, with his characters turning their lives into a permanent spectacle. In lectures on film and media theory, “The 10th Victim” is often discussed in connection with Guy Debord’s concept of the “society of the spectacle” or Jean Baudrillard’s ideas on hyperreality.

The 10th Victim has also left its mark on film history: many see it as the conceptual precursor to Battle Royale (2000), The Running Man (1987), and The Hunger Games (2012). Directors such as Paul Verhoeven and Terry Gilliam have cited Petri as an influence, particularly because of his ironic treatment of violence and consumerism. Films such as The Truman Show and Black Mirror also take up similar themes—surveillance, self-expression, and the aestheticization of death—and carry Petri’s ideas into the digital age. In retrospect, The 10th Victim thus becomes a central link between classic dystopia and postmodern media criticism.

The visual language—shiny surfaces, cold architecture, bright colors—later influenced films such as A Clockwork Orange and The Man Who Fell to Earth. The film is also a document of the changing gender image of the 1960s: Andress‘ character embodies an aggressive, self-determined femininity, while Mastroianni appears as a deconstructed image of masculinity. This play with gender roles is now considered a feminist subtext that was far ahead of its time. Some critics compare Andress‘ Caroline to modern anti-heroines such as Furiosa from Mad Max: Fury Road or Beatrix Kiddo from Kill Bill – strong but ambivalent characters who combine power and vulnerability. Thus, The 10th Victim remains a fascinating hybrid of style, satire, and sociocultural analysis to this day.

Conclusion

“The 10th Victim” is a piece of retro-futurism with bite – a wild mix of sci-fi, comedy, social satire, and mod aesthetics. Petri manages to turn a simple premise into a scathing parable about fame, death, and the human longing for meaning. In doing so, he not only sketches an ironic vision of the future, but also a portrait of his present – an era in which glamour and violence form an ominous alliance. Behind the colourful surface lies a razor-sharp analysis of the Western attitude to life in the 1960s: a mix of prosperity, boredom and the urge to show off. Petri stages this with a smile that is never entirely without bitterness.

What today looks like an ironic commentary on the times was visionary at the time: a world in which media, commerce, and violence merge inseparably. The film remains a fascinating example of how style and substance can reinforce each other—flashy, provocative, and yet astonishingly prescient. Its themes—the hunger for attention, the transformation of the individual into a brand, and the devaluation of human relationships—seem even more relevant today than they did in 1965. In an era in which social media is turning life into a permanent spectacle, Petri’s film reads almost like a prophetic warning. Its aesthetics, which play with pop art and irony, also prove to be astonishingly modern: every shot, every costume, every color choice speaks of the conflict between authenticity and superficiality.

Or, in other words: Before people played for their lives in the cinema, they were already doing so on television – made in Italy. This final ironic twist encapsulates the essence of the film – a reminder that entertainment is always a mirror of society. “The 10th Victim” thus remains a work that provokes thought without losing its lightness, a film that dances between satire and philosophy, unforgettably demonstrating that style can sometimes be the most honest form of criticism.

More

Trailer

External links

Hashtag: The10thVictim #ElioPetri #1960sSciFi #Swingpunk #MediaViolence #PopArtCinema #BattleRoyalePrecursor #UrsulaAndress #MarcelloMastroianni #FilmAnalysis #CultCinema #FuturisticAesthetics #ConsumerismCritique #MovieReview #RetroSciFi

Keywords: The 10th Victim film analysis, The 10th Victim 1965 review, Elio Petri The 10th Victim themes, Battle Royale precursor cinema, Swingpunk 1960s science‑fiction film, Ursula Andress Marcello Mastroianni The 10th Victim, Big Hunt concept The 10th Victim, Media violence and spectacle film 1960s, Pop art aesthetics in The 10th Victim, Consumerism and violence in 1960s film

Kommentar verfassen :