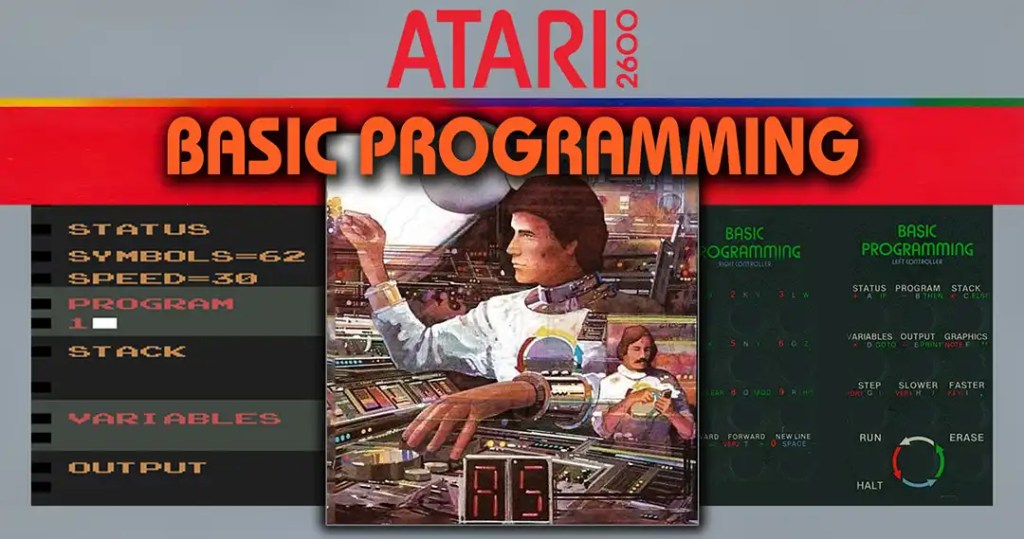

BASIC PROGRAMMING

is an instructional tool designed to teach you the fundamental steps

of computer programming. BASIC is an It is an acronym for

‚Beginner’s All-Purpose Symbolic Instruction Code‘

It was created so that people could easily

learn to write computer programs.

Basic on a Game Console

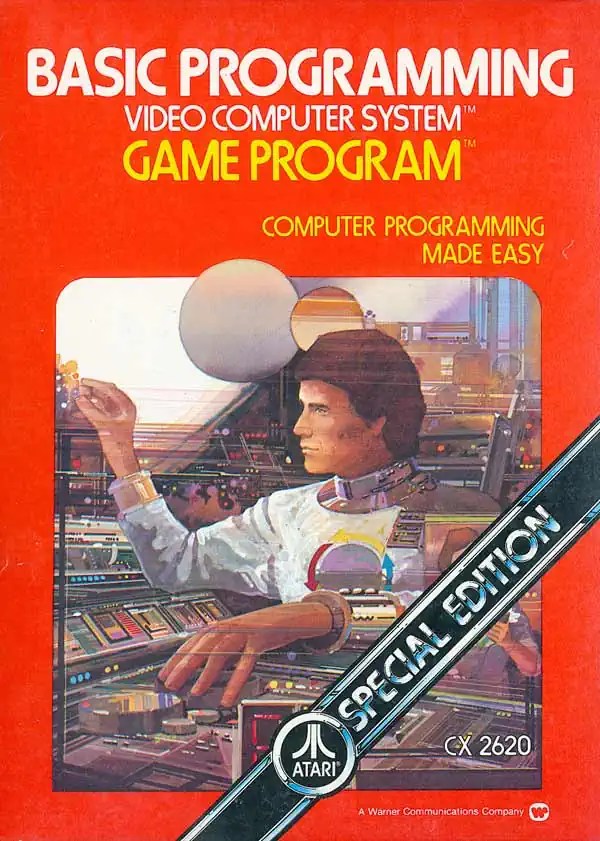

BASIC Programming is an unusual and fascinating piece of video game history. In 1979, just two years after the release of the Atari Video Computer System (VCS, later known as the Atari 2600), Atari ventured into an experiment that was far ahead of its time. While the VCS was known for its action-packed games such as Space Invaders, Combat, and Adventure, a cartridge suddenly appeared that was not a game in the traditional sense, but rather a tool for programming. In an era when the term “coding” still sounded exotic to most people, Atari attempted to transfer the concept of programming to a pure game console. The result was ambitious, visionary – and technically very limited. Nevertheless, it marked one of the earliest attempts to introduce console users to the idea of “self-design.”

What can you do with it?

With “BASIC Programming,” users could write their own programs, albeit in a greatly simplified version of the popular language BASIC (“Beginner’s All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code”). This language was originally developed to make computers more accessible to beginners and was widely used on home computers and university computers in the 1970s. With this module, Atari wanted to bring a part of this world into the living room TV. The complex BASIC system was reduced so much that only elementary commands remained – a kind of “Mini-BASIC” that was broken down to the absolute minimum.

The aim was to teach basic programming logic – such as how to perform calculations, output text or create simple decision structures – but also to develop an initial understanding of how a machine reads and executes commands. The module was designed to teach users how to break down problems into logical steps and plan simple sequences, providing a playful introduction to what was then a completely new way of thinking. For many, this was their first experience of “talking to the machine” – a moment that combined the magic and frustration of early computer interaction.

The possibilities included:

- Performing small arithmetic operations, such as addition or multiplication

- Outputting short lines of text, for example “HELLO WORLD”

- Simple logical sequences with conditions (‘IF’) and repetitions (“FOR” loops)

- Defining simple variables to store values

But despite its theoretical flexibility, putting it into practice was difficult. Only about 64 bytes of RAM were available for custom programs—less memory than a tweet today. This tiny amount of memory meant that every letter, number, and command had a noticeable impact on capacity. Each input had to be carefully planned, as memory and input options were quickly exhausted and the system had no error tolerance. One wrong keystroke could mean that the entire program had to be restarted. Even a simple calculator was difficult to implement completely because after a few lines there was no more space for further operations. Some users found creative ways to squeeze out a few extra bytes through clever abbreviations or clever reuse of variables. Nevertheless, working with such limitations was more an exercise in patience than in functionality. Despite this, the module gave many users their first taste of giving commands to a machine and thereby creating something themselves, a small but significant step toward an interactive, creative approach to technology.

Examples of simple programs that were possible on the system might have looked something like this:

10 PR. “HELLO WORLD”

20 END

A classic example that simply outputs text.

10 IN. A

20 IN. B

30 PR. A+B

A small calculation program that reads two values and displays their sum.

10 FOR I=1 TO 5

20 PR. “ATARI!”

30 NEXT I

A simple loop that outputs the word several times – early evidence of repetition structures in BASIC programming.

10 IN. N

20 PR. “MULTIPLICATION TABLE FOR ”;N

30 FOR I=1 TO 10

40 PR. I;“ X ”;N;“ = ”;I*N

50 NEXT I

60 END

This more comprehensive example calculates and displays a small multiplication table for a number entered by the user. It combines input, loops, variables, and simple arithmetic operations – demonstrating the limitations, but also the versatility, of BASIC programming on the Atari VCS.

Technology

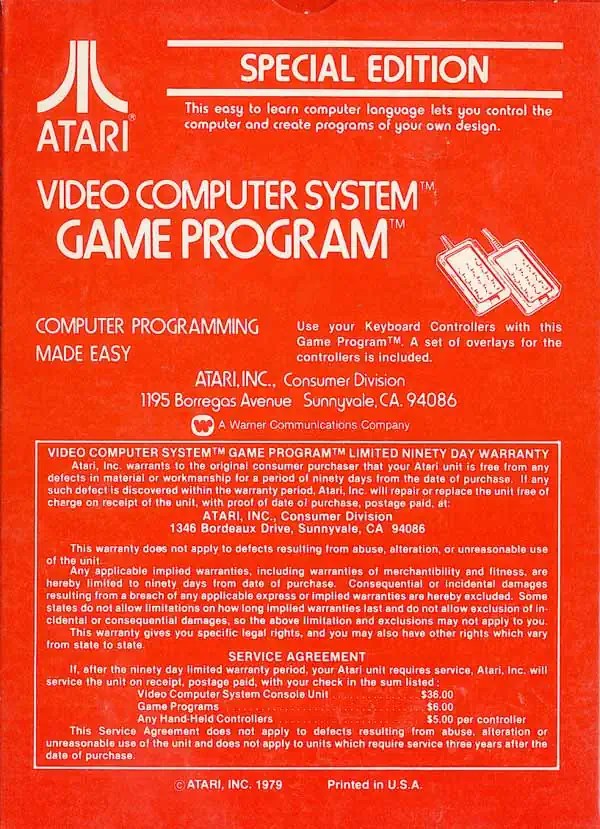

The module itself was based on a 4-kilobyte ROM, which was typical for the time. This capacity corresponded to the technical limitations of the Atari VCS system, which offered only very limited memory and processor power anyway. But unlike games that used joysticks or paddles, “BASIC Programming” required two special keyboard controllers. These resembled numeric keypads, each had twelve keys, and worked with interchangeable plastic foil overlays that explained which keys represented which letters, numbers, or commands. Depending on the desired mode, the player had to apply a different overlay – a cumbersome but creative way to simulate the function of a real keyboard.

Code was therefore not typed in using a keyboard, but via a kind of symbolic input matrix – a laborious process that required a lot of patience. Each command had to be composed of several keystrokes, as many characters and commands were achieved through nested multiple combinations. Anyone who wrote a few lines of code often spent minutes just to enter one line correctly. Furthermore, there was no way to delete or edit commands without rewriting parts of the program. These limitations made programming an almost meditative activity in which concentration, planning, and perseverance were more important than speed. Some players found this challenging, others found it unreasonable, but everyone learned the hard way how precise and disciplined programming could be.

A three-part interface appeared on the screen:

- Text field: This is where the lines of code were displayed. Only a few lines could fit on the screen at a time, which made editing difficult.

- Variable and memory display: Here you could see the current state of the variables and the remaining memory space – an important aid for planning.

- Command line: This area was used to enter instructions, which were then interpreted and executed.

The syntax was extremely reduced. Many BASIC commands were shortened to one or two letters to save memory and reduce input time, creating a kind of minimalist “programming vocabulary.” For example, “PR.” was used for “PRINT,” “IN.” for “INPUT,” and logical operators such as “IF” were retained, albeit with severely limited comparison functions. Simple control structures such as ‘GOTO’ or “FOR” were also available, albeit in a slimmed-down form and usable only within narrow limits. So anyone who wanted to write more complex programs had to resort to clever workarounds, such as combining several commands in one line or overwriting variables to save memory space.

One example of this is that it was not possible to create nested loops or subroutines; all processes had to be linear and controlled manually. Nevertheless, this reduced syntax conveyed a basic idea of how programming languages are structured: with commands, parameters, and logical conditions. Players learned through trial and error which sequence of commands led to which results—a kind of experimental learning that later helped many to switch to full-fledged BASIC interpreters. Complex program structures or loops spanning multiple lines were practically impossible, but the learning effect remained: users got a feel for how logic and sequences determine the behavior of a machine.

Trivial

- “BASIC Programming” was one of the very few non-gaming modules for the Atari VCS – an absolute exception in the range. Atari itself promoted it at the time as a teaching tool and a step toward “computerizing” the living room, an attempt to expand the Atari console from a pure gaming device to a learning machine.

- The module included a comprehensive manual that explained not only how to use it, but also basic programming principles – an early example of “edutainment.” It was richly illustrated, full of examples, and even included small programming tasks reminiscent of school exercises. For many children and teenagers, this was their first contact with the concept of algorithmic thinking.

- Ironically, the module was not compatible with real BASIC versions on home computers such as the Atari 400/800, Apple II, or Commodore PET. The simplified syntax was completely proprietary, making it more of an “introduction to ways of thinking” than a real programming language. This incompatibility meant that many users were later surprised at how differently real BASIC worked when they switched to home computers.

- Due to the limitations, many of the programs shown in the manual could not be fully implemented – they were merely for illustrative purposes. Some instructions described hypothetical routines that required more memory or screen lines than the VCS could provide. Nevertheless, they encouraged reflection and experimentation, and some enthusiasts tried to implement these concepts on real computers as soon as they had access to them.

- The cartridge was produced in relatively small quantities, making it a sought-after collector’s item today. Particularly well-preserved copies with original overlays and manuals fetch high prices on the collectors‘ market. Some retro enthusiasts consider it not just a curiosity, but an important step in the history of digital education—a symbol of the moment when gaming began to open up to learning.

Criticism at the time

Reactions to “BASIC Programming” were mixed to lukewarm. Contemporary reviews praised the educational aspirations and creativity behind the idea, but considered the implementation to be virtually unusable. Many critics described the module as a “well-intentioned concept with no practical value” because it overwhelmed the capabilities of the Atari VCS and was far too cumbersome to use. Trade journals criticized in particular:

- the cumbersome input system via the controllers,

- the lack of a program save function,

- the tiny memory space, which hardly allowed for any meaningful experiments,

- and the lack of any visual or auditory feedback.

Some testers noted that the learning curve was steep and that beginners quickly became discouraged because their programs often did not work or had to be restarted due to minor typos. Nevertheless, many journalists recognized the underlying vision and praised Atari for attempting to turn the user into a “creator” – an idea that seemed radical at the time.

Many players found the module interesting but frustrating – a technical exercise with no practical use. It was more of an experiment than a real tool, and many gave up after a short time. Some parents, however, saw it as an opportunity to teach their children logical thinking and the basics of computer science in a playful way, long before computer lessons were established in schools. The manual attempted to guide the learning process, but without a keyboard and with constant error messages, patience was required. Some early users reported that the module was what first sparked their interest in home computers, and they later switched to systems such as the Commodore 64 or Apple II.

Despite the criticism, BASIC Programming was cited in some collections and teaching contexts as evidence that early console manufacturers recognized the educational function of digital devices—albeit clumsily implemented. Later reviews in retro magazines and online archives described the game as “a bold failure” that was ahead of its time and opened the door to a new kind of interaction. In this sense, it is now regarded not as a failed game, but as a culturally significant experiment.

Cultural influence

In retrospect, “BASIC Programming” occupies a special place. Commercially, it was not a success, but conceptually, it laid the foundation for the idea that consoles could be more than just passive entertainment machines, but potential tools for creativity. In the following years of the 8-bit era, programs and games such as The Quill for the ZX Spectrum, Pinball Construction Set or Racing Destruction Set on the Commodore 64, and Music Construction Set took up similar concepts: The player becomes the developer, the game becomes the development environment.

For technology enthusiasts in the late 1970s, the module was a window into a world that soon became popular through home computers such as the Commodore 64, ZX Spectrum, and Atari 800. It showed that interactive systems could be used not only for entertainment, but also for education and creative expression. Many later programmers mention that modules like this gave them their first contact with the idea of programming – even if they achieved hardly any useful results, it sparked their fascination with teaching machines logical processes. Some say they spent hours crafting small works of art or random text outputs from a few lines of code, just to see “what happens.”

In retro circles, “BASIC Programming” is now considered a symbol of the early spirit of experimentation and proof that even on the simplest hardware, the desire for control and creativity existed. It is often referred to as the precursor to modern “maker” culture, a movement that sees humans as active designers of their technology. Historians emphasize that it was less about the specific programs that could be written and more about the feeling of having created something yourself – an idea that lives on in today’s digital culture, from open-source development to game design tools.

Conclusion

“BASIC Programming” for the Atari VCS was far ahead of its time – and at the same time a victim of its technical limitations. It was less a practical tool than proof that even a game console could theoretically be programmable. For Atari, it was an attempt to venture into interactive education rather than purely entertainment electronics – a precursor to what we would now call “creative computing.” The project demonstrated that even in the late 1970s, there was already an idea of allowing users to actively intervene in the functioning of the medium rather than just consume it. In a way, it can be said that “BASIC Programming” aroused the same curiosity and desire to experiment that later came to fruition in the home computers of the 8-bit era, for example when learning BASIC on the Commodore 64 or tinkering with machine commands on the ZX Spectrum.

Today, the module is primarily appreciated by collectors, retro fans, and technology historians. It symbolizes the courage to try new things, even if the result is not yet fully developed. Many see it as a kind of lesson about the limits and possibilities of digital creativity. In museums and retro exhibitions, it is often shown as an example of how closely gaming, learning, and technological innovation were intertwined. “BASIC Programming” shows that early on in the history of digital gaming, there was already the idea of letting players not only consume but also create – an idea that lives on today in countless creative games, learning systems, and software construction kits, from early 8-bit editors to modern game engines that carry on this spirit in a contemporary form.

More

Longplay

External links

keyword: Atari 2600 BASIC Programming, Atari VCS programming cartridge, Atari 2600 educational software, early home computing programming on consoles, retro gaming programming experiments, Atari edutainment cartridge, 8‑bit console programming history, Atari VCS BASIC module, home computer programming 1970s consoles, GenXGeek retro computing, Beginner’s All-Purpose Symbolic Instruction Code on console, Mini‑BASIC on Atari, Atari 2600 keyboard controller accessory, console becomes creative tool, retro edutainment hardware, history of game consoles programming, Atari 2600 collector’s item, programming logic loops IF FOR Atari

Hashtags: #Atari2600 #AtariVCS #RetroGaming #HomeComputing #Edutainment #ProgrammingHistory #MiniBASIC #GenXGeek #VintageTech #GameConsoleHistory #MakerCulture #8bit #ConsoleProgramming

Kommentar verfassen :