How does it feel like to be out of control?

Introduction

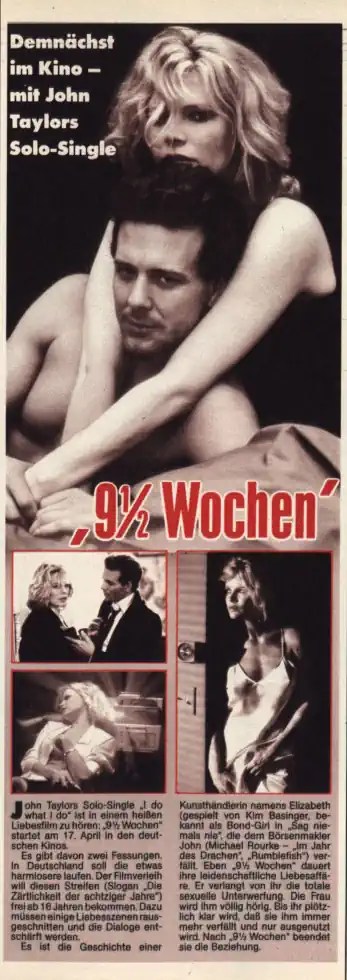

“9 1/2 Weeks” is a 1986 American erotic drama directed by Adrian Lyne. The film was made at a time when mainstream cinema was increasingly willing to portray sexuality in a more explicit yet highly stylized manner and to stage intimate relationships as visual spectacles. In the 1980s, the portrayal of eroticism in cinema shifted noticeably: between artistic aspirations, commercial interests, and social provocation, filmmakers sought new forms of expression. In this field of tension, 9 1/2 Weeks positioned itself as a work that radically combined aesthetics and emotionality.

Despite an initially cautious to critical reception by the press and audience, the work developed over the years into a cult classic of the 1980s. This was largely due to its unmistakable, aesthetically composed visual language, its atmospherically dense soundtrack, and its uncompromising portrayal of an obsessive, emotionally asymmetrical relationship. Added to this was the intense presence of the lead actors, whose interplay contributed significantly to the film’s lasting impact.

The film is exemplary of an era in which glossy visuals, urban coolness, and erotic tension merged and were condensed into elaborately composed images. New York appears not only as a setting, but as an atmospheric resonance chamber for isolation and desire. In doing so, “9 1/2 Weeks” constantly walks the fine line between fascination and disturbance, between aesthetic seduction and emotional coldness. It was precisely this ambivalence that made it both attractive and irritating to many viewers and contributed to its remaining anchored in the cultural memory beyond the time of its creation.

Another key factor in the film’s enduring fascination is its distinctive 1980s look. The visual style is characterized by soft focus shots, warm gold and brown tones, high-contrast neon lighting, and an overall glamorous, slightly otherworldly aesthetic. The fashion and styling clearly reflect the spirit of the times: elegant suits with broad shoulders, silk blouses, high-waisted pants, and deliberately staged business elegance underscore the urban lifestyle of the decade. The interiors—minimalist lofts, reflective glass surfaces, steel, and leather—also convey an image of cool modernity and luxurious distance. In combination with the synthetic soundtrack, this creates a sensual overall picture that firmly anchors the film in the cultural climate of the 1980s and decisively shapes its unmistakable look and feel.

Plot

The plot centers on gallery owner Elizabeth McGraw, who lives and works in New York. She moves in Manhattan’s creative scene, surrounded by works of art, vernissages, and intellectual conversations, and appears self-determined and confident to the outside world. Her everyday life is characterized by routine, professional competence, and a certain controlled distance from other people. Behind this façade, however, there is a hint of an emotional void – a longing for intensity, for an experience that goes beyond the ordinary. When she meets the mysterious and wealthy investment banker John Gray, this fragile balance is shaken.

An intense affair ignites between the two, dominated from the outset by a strong physical attraction, which quickly develops into an all-consuming experience. John stages the relationship as a series of controlled situations that appear less random and more carefully arranged.

He determines the place, time, and sequence of their meetings, choosing luxurious hotel rooms or anonymous-looking apartments, thus creating spaces that lie outside Elizabeth’s familiar world. As she increasingly engages in a game of seduction, power, and submission, the dynamic steadily shifts in favor of his control. Step by step, he leads her into a world of erotic experimentation, where boundaries are deliberately crossed and taboos are explored in a playful but calculated manner. It becomes increasingly clear that John is less interested in intimacy or emotional openness than in exercising influence and testing his power.

What at first seems exciting and liberating, giving Elizabeth the feeling of leaving old patterns behind, gradually develops into a psychological ordeal. The intensity of the encounters leaves little room for reflection; passion and insecurity are closely intertwined. Elizabeth vacillates between lust, curiosity, and growing unease, between the desire to let herself go and the fear of losing control of her own life. John’s emotional distance—his refusal to reveal personal background or show genuine vulnerability—stands in stark contrast to her increasing inner dependence. The more she commits herself, the more he withdraws.

The relationship lasts—as the title suggests—nine and a half weeks and unfolds like an intense state of emergency that increasingly supplants reality and everyday life. Friends, work, and social obligations fade into the background. Finally, the affair culminates in a moment of self-awareness: Elizabeth realizes that she is beginning to lose herself in this dynamic, that her desires and boundaries are increasingly being overshadowed by John’s ideas. Her decision to end the relationship is therefore not only a farewell to a passionate episode, but a conscious act of self-assertion and regaining her autonomy.

Actors

The leading roles are played by Mickey Rourke as John Gray and Kim Basinger as Elizabeth McGraw. Rourke imbues his character with a mixture of cool elegance, enigmatic reserve, and latent threatening dominance. His performance is reduced, often minimalistic, which reinforces the impression of emotional impenetrability and at the same time creates a permanent tension. With sparse facial expressions and controlled body language, he creates a character who exercises his power less through volume than through subtle presence. John remains a mystery for long stretches – a man whose motives are never fully revealed and whose past remains in the dark. It is precisely this vagueness that makes him both fascinating and unsettling.

Kim Basinger, on the other hand, portrays Elizabeth as a multi-layered character whose emotional journey is at the heart of the film. She convincingly shows her development from initial fascination to passionate devotion to inner turmoil and growing uncertainty. Her performance is physically and emotionally intense; she credibly conveys how strongly attraction and doubt can intertwine. Especially in the quieter moments—in glances, hesitant gestures, or moments of pause—she succeeds in making vulnerability and doubt palpable. Her performance contributes significantly to the film being perceived not only as an erotic spectacle, but also as a psychological drama that focuses on a woman’s inner development.

The chemistry between the two actors is still considered a central element of the film today. The interplay between Rourke’s controlled coolness and Basinger’s emotional openness creates a dynamic that goes far beyond pure physicality. The so-called “refrigerator scene,” in which eroticism, play, and symbolic exercise of power collide, became particularly famous. This sequence, which works with sensory impressions, music, and close-ups, became an iconic moment in 1980s film history and has been quoted and parodied many times. It exemplifies the aestheticized yet ambivalent portrayal of intimacy that characterizes the entire film.

Trivia

The film is loosely based on the autobiographically inspired novel of the same name by Elizabeth McNeill. The literary source material also depicts an intense, dominance-oriented relationship, but its tone and perspective differ in some respects from the film adaptation. While the novel is told more from the subjective inner perspective of the female character and illuminates her thoughts in detail, the film relies more on visual condensation and symbolic imagery. This shifts the focus from literary self-reflection to an aestheticized portrayal of power and desire that offers more suggestion than explicit explanation.

According to reports, tensions arose between the lead actors during filming. Some sources say that director Adrian Lyne deliberately worked with emotional distance and improvisation in order to elicit authentic reactions and capture spontaneous moments. This approach is said to have resulted in certain scenes being shot without full consultation, with the actors performing in a state of real uncertainty. Although such methods are controversial and must be viewed in a differentiated manner from today’s perspective, they may have contributed to the palpable intensity of many scenes and reinforced the impression of a relationship characterized by unpredictability.

The soundtrack also played a decisive role in the film’s impact. Songs such as “You Can Leave Your Hat On” by Joe Cocker became inextricably linked to certain scenes and developed a life of their own in pop culture. The music functions not only as background, but as a narrative element that significantly shapes the mood, rhythm, and emotional tension. The deliberate use of blues, rock, and synthesizer sounds creates an atmosphere between sensuality and melancholy. Many sequences rely more on light, shadow, slow motion, and background music than on dialogue, making the film seem at times almost like a visually composed music video that conveys emotions through images and sounds.

Criticism at the time

When it was released in theaters, “9 1/2 Weeks” received mostly mixed to negative reviews. Numerous reviewers criticized the supposed superficiality of the characterization and the aestheticized portrayal of a problematic relationship dynamic. Critics argued that the psychological backgrounds of the characters were only hinted at but not sufficiently explored, which made central motifs of the plot seem schematic. In particular, the question of whether the film romanticized emotional manipulation or at least trivialized it was controversially discussed. Feminist voices accused the work of staging a power imbalance that was presented more as an erotic stimulus than as a problematic structure.

Others, however, praised the visual design, the consistent stylistics, and the courage to portray sexuality in a mainstream film in such an explicit and at the same time artistic way. Proponents emphasized that the film should be understood less as a realistic study of relationships and more as a stylized fantasy that deliberately works with exaggeration and symbolism. The camera work, the play with mirrors, shadows, and urban architecture were praised as expressions of a new form of erotic cinema that functions more through atmosphere than dialogue. The combination of music and images was also described as innovative and considered influential for an entire generation of filmmakers.

Commercially, the film initially fell short of expectations in the US, which was partly attributed to controversial press coverage and inconsistent marketing. In Europe, however, particularly in France and Germany, it quickly became a box office success and enjoyed an above-average run in cinemas. European audiences were more open to the aestheticized portrayal of eroticism and interpreted the film more as a stylish relationship drama than as a mere erotic film. These different reactions underscored how much cultural contexts can shape the perception of a work.

Cultural influence

In retrospect, “9 1/2 Weeks” is considered a style-defining film for the erotic drama genre. The combination of glossy aesthetics, urban melancholy, and explicit sensuality influenced numerous productions in the late 1980s and 1990s and helped establish a new visual language for cinematic intimacy. Motifs such as the play with power imbalances, the fascination with emotional borderline experiences, and the staging of sexuality as psychological terrain were revisited in many ways in later films and series. The work often served as a reference point for directors who wanted to explore similar tensions between desire and control. The aesthetic exaggeration of everyday spaces—apartments, elevators, street canyons—was also adapted and further developed in many ways.

In addition, the film had a lasting impact on pop culture. Image compositions with candlelight, half-shaded faces, and slowly staged touches became visual codes for passionate but dangerous relationships. This visual symbolism found its way into music videos, advertising campaigns, and photo series that deliberately picked up on the mixture of glamour and emotional coldness. Even the fashion and advertising aesthetics of the late 1980s reflected the influence of the film by working with similar contrasts of light and shadow and an emphatically sensual staging. In this way, “9 1/2 Weeks” transcended the boundaries of cinema and became part of a broader cultural style.

Last but not least, “9 1/2 Weeks” is often reevaluated in the context of debates about consent, power structures, and gender roles. While the film was primarily considered provocative or scandalous in the 1980s and attracted attention mainly because of its explicit scenes, today the psychological dimension of the relationship is more the focus of analysis. Contemporary discussions ask to what extent the dynamics depicted reproduce problematic patterns or consciously reflect them critically. This has changed the reception of the film: it is no longer seen merely as an erotic document of its time, but also as a starting point for a nuanced examination of intimacy, power, and self-determination.

Conclusion

“9 1/2 Weeks” is much more than just an erotic drama. The film tells a story of power, desire, and emotional dependence, of longing for closeness and the danger of losing oneself in a passionate relationship. At the same time, it paints a portrait of two people who, in their encounter with each other, find less fulfillment than a reflection of their own inner conflicts. Its stylistic consistency, the deliberate reduction of psychological explanations in favor of suggestive images, and the intense portrayal of the main characters made it a work that transcends its time of origin and can still be interpreted in different ways today.

Despite—or perhaps because of—its controversial reception, the film has established itself as a cult classic. It remains a striking example of how cinema can simultaneously seduce, disturb, and stimulate discussion. In retrospect, it appears as a document of the 1980s that brings together aesthetic trends, fashion codes, and social tensions, but can also be read as a universal study of passion and loss of self. Its distinctive 1980s style—with glamorous coolness, stylized interiors, and an unmistakable sound between rock and synthesizer—contributes significantly to the fact that the film is still immediately associated with a specific era today. Thus, “9 1/2 Weeks” asserts its firm place in film history—as a work that not only provoked, but also aesthetically shaped an entire decade with its unmistakable “look and feel” and sparked lasting debates about intimacy and power.

Kommentar verfassen :