Alone at the bottom of a narrow stairway, in a deserted

mansion at the edge of town, you come upon an ancient mystery – and

the beginning of a strange new adventure…

The forgotten gem of the 8-bit era

In 1985, Lucasfilm Games (now known as LucasArts) released the game “The Eidolon” for various home computers such as the Commodore 64 (C64), Atari 8-bit, and MS-DOS. In an era of pixelated graphics and simple sound chips, the game stood out for its unusually dark style and ambitious technology. As the successor to the game “Rescue on Fractalus!”, “The Eidolon” once again used so-called “fractal technology” – this time not for alien planets, but for mystical cave systems full of monsters, magic, and secrets.

The game did not follow a conventional plot pattern, but relied on subtle visual clues and a progressive discovery of the game world. Unlike many titles of its time, which strictly adhered to arcade or platform concepts, The Eidolon conveyed a sense of exploration and uncertainty. The player did not know what to expect at the beginning – a concept that later games such as Myst and Metroid picked up on and developed further.

The appeal of the game lay not only in its technical innovation, but also in its atmospheric depth. The mixture of steampunk aesthetics, surreal creatures, and a mystical setting made the game stand out from the crowd of action and platform titles. Visual elements such as the pulsating glow inside the Eidolon or the eerily empty corridors of the caves created a unique atmosphere that oscillated between fascination and menace.

At a time when many games were dominated by linear level structures and simple mechanics, The Eidolon was a bold step toward an immersive gaming experience. It required patience, observation skills, and a certain amount of imagination—qualities that were not part of the standard repertoire of many games at the time. Lucasfilm Games‘ decision to implement such an unconventional concept speaks to the experimental spirit that characterized the studio in the 1980s.

Gameplay

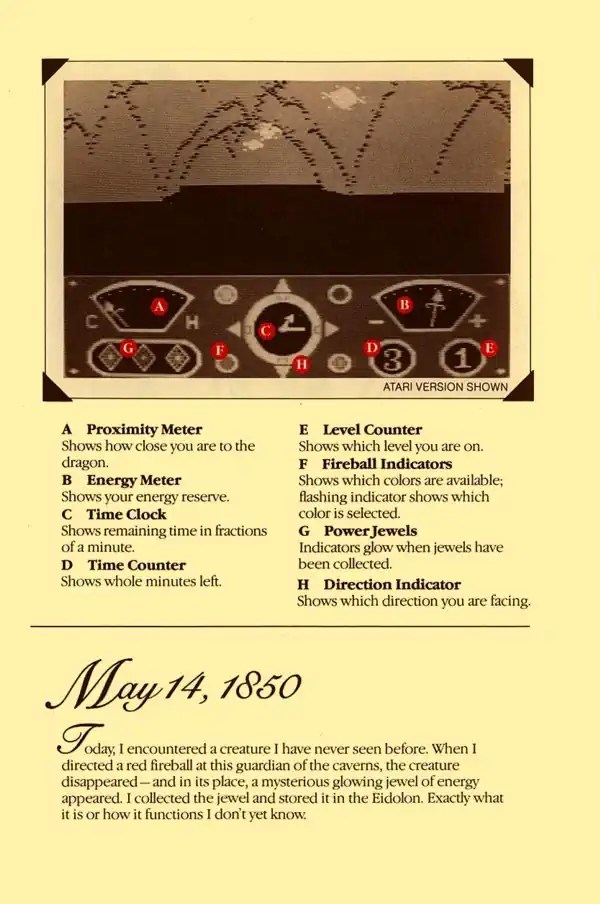

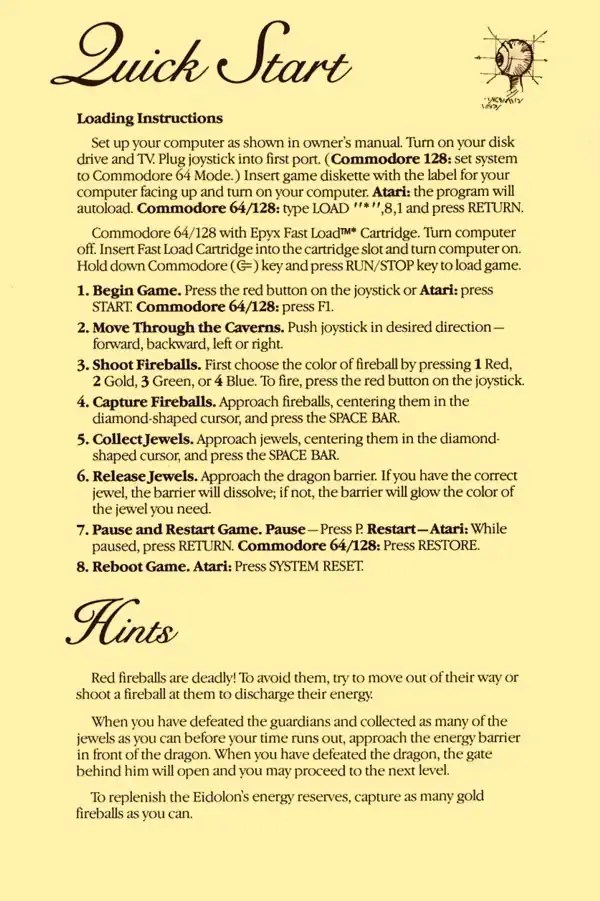

The Eidolon puts the player in the role of an unnamed protagonist who controls a strange steam-powered machine – the eidolon that gives the game its name. In this machine, the player moves through a system of 3D caves, collecting energy, avoiding dangers, and fighting mysterious creatures with colored fireballs. The focus is less on hectic action and more on calm, almost deliberate movement. The controls take some getting used to, but they are tactically challenging and reward forward thinking.

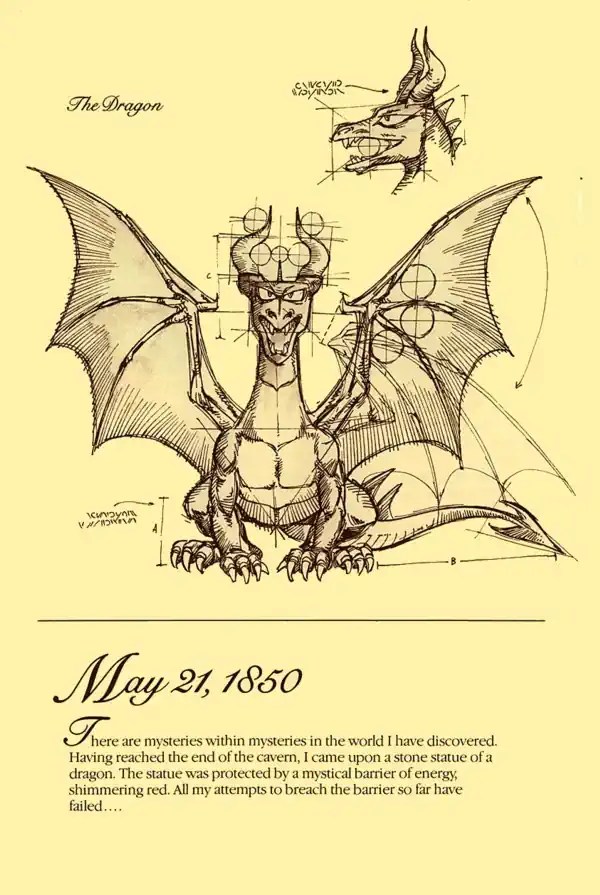

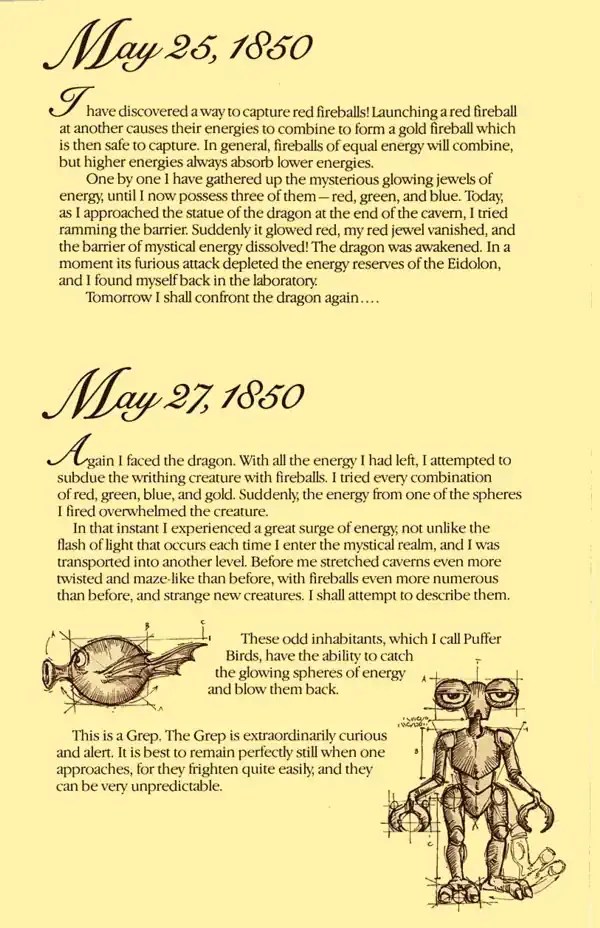

The game is divided into eight levels, each guarded by a dragon. These dragons act as boss enemies and each presents its own challenge, both visually and in terms of behavior. The levels become increasingly complex, with more challenging enemies and trickier navigation tasks. Apart from the main enemies, all kinds of bizarre creatures roam the cave systems – ghosts, golems, tentacled creatures, floating eyes, and mutated insects – each with their own attack patterns and movement types. A central element is the collection of different colored energy balls, which are used to charge fireballs with different effects. These are necessary to defeat certain enemies, activate protective shields, or open locked passages.

Energy management is a constant issue: movement, the use of weapons, and the collection of objects all cost energy. If your supply is exhausted, it’s game over. This adds a strategic component to the game – you can’t blindly collect or shoot everything, but must weigh up what makes sense and when. In addition, there are hidden energy sources that can only be discovered through careful observation or by chance. Some rooms even contain puzzles or switches that allow you to progress further – a mechanic that was far ahead of its time.

A particularly fascinating aspect is the navigation: the player moves in a kind of pseudo-3D world, with changes in perspective and rudimentary depth – an absolute rarity on the C64. The corridors seem alive, even though they are graphically minimalistic. This effect is achieved through the clever use of color changes, flickering effects, and targeted shadows. This creates a sense of depth and presence that is rarely experienced on 8-bit systems. Orientation is deliberately kept vague – without a map or clearly recognizable signposts, players must remember for themselves where they have already been and which paths they have not yet explored. This element contributes greatly to the atmosphere and underscores the exploratory nature of the game.

Technology

Technically, The Eidolon was far ahead of its time. It used a fractal graphics engine that was originally intended for terrain rendering. Instead, it was repurposed here to simulate a seemingly “rotating” three-dimensional cave environment – a stroke of genius that made use of the limited resources of the C64. The fractals allowed the creation of complex, labyrinthine structures with little memory requirements. In addition, this technology enabled an almost unlimited variation of cave systems without relying on large data sets – a clever method of memory optimization and resource reusability.

The graphics are atmospherically dark, with flickering animations, sprite-based monsters, and surprisingly fluid movement. The colors are deliberately reduced, creating a feeling of menace and isolation. Particularly noteworthy is the way color changes and visual effects were used to simulate a sense of depth and movement. Light and shadow transitions reinforce the feeling of disorientation, which fits the setting perfectly. The visual design is a successful example of how much can be achieved with limited resources.

The sound is sparse but effective: muffled noises and ghostly tones underscore the eerie atmosphere. There is hardly any music in the conventional sense, which reinforces the feeling of loneliness in the game. Instead, the sound design works with subtle acoustic cues that blend into the atmosphere. Sounds such as the soft hiss of an approaching enemy or the metallic echo of a fired fireball increase immersion and also serve as feedback for the gameplay.

The controls – especially switching fireball colors and aiming – were a bit clunky, but they were implemented quite respectably within the limits of what was possible at the time. Many players needed several attempts to get used to the sluggish but realistic controls. Interestingly, it was precisely this sluggishness that contributed to the atmosphere: it conveyed the feeling of controlling a heavy, steam-powered machine rather than a light game character. But those who embraced it were rewarded with a deep gaming experience that relied more on strategy, observation, and tactics than on reflexes – a feature that gave the game a special depth.

Trivia

- The Eidolon was one of the first games to use fractals for interiors rather than landscapes. This reversal of the usual usage opened up completely new creative possibilities in level design. The narrow, branching tunnels appeared alive and organically grown thanks to the fractal logic – an effect that would have been difficult to achieve with traditional techniques.

- The packaging and manual were elaborately designed – typical for Lucasfilm games – and included background stories and illustrations that embedded the gameplay in an atmospheric setting. Particularly striking were the pseudo-scientific drawings and notes that gave the game a believable fictional world, similar to what was later seen in games such as BioShock or Dead Space.

- The name “Eidolon” comes from Greek and means ‘mirage’ or “ghostly apparition.” This fits perfectly with the overall mood of the game, which features hallucinations, light illusions, and surreal enemies. The choice of name underscores the ambition to create not just a game, but an atmospheric experience.

- Many of the enemies in the game were based on concept drawings by the Lucasfilm design team, which also created sketches for film projects such as Star Wars. This artistic heritage gives the creatures a particularly cinematic, well-thought-out look – a far cry from the often simplistic sprite enemies of the time. Some designs were even reused in later film projects or served as a source of inspiration for effects and scenarios.

- The level structure follows a spiral progression: players repeatedly return to similar cave sections, but with new enemies or more difficult conditions. This concept creates a sense of recognition that is constantly broken by new elements – an approach that builds psychological tension and keeps the player in a state of constant unease. It also increases the replay value, as players try to discover all the variations and changes.

- Furthermore, some versions of the game included hidden Easter eggs and graphical gimmicks that could only be discovered through unusual behavior or precise timing – a kind of early “developer humor” that further fueled the myth surrounding The Eidolon.

Criticism at the time

Contemporary reviews were mixed – while many magazines praised the graphics and innovative technical approach, several reviews criticized the gameplay as “too repetitive” or “confusing.” In particular, the high level of difficulty, coupled with the unusually sluggish controls, presented a barrier for many players. Some found the gameplay frustrating, as trial-and-error passages and disorientation were common. Nevertheless, The Eidolon was not considered a failure by the trade press and gaming community. On the contrary, many praised its courage to innovate and its atmospheric depth, which clearly set it apart from the competition. Particular emphasis was placed on the feeling of experiencing something completely new – a game that could not be pigeonholed into existing genres.

The technical implementation was also hailed as a milestone. At a time when games were often characterized by simple graphics and one-dimensional gameplay mechanics, The Eidolon offered a surprisingly immersive experience. The 3D-like representation of the cave systems and the use of fractal algorithms were considered groundbreaking. Critics who defended the game saw it less as a classic action game and more as an audiovisual experiment with playful elements – an interactive work of art that unfolded its effect in a rather subtle way.

Opinions varied greatly depending on the audience. While hardcore action gamers were often disappointed by the leisurely pace and indirect controls, experimental gamers and technology enthusiasts found The Eidolon to be a fascinating object of study. Especially in English-speaking countries, the game was often associated with the term “visionary.”

Cultural influence

The Eidolon never became a mass phenomenon like Maniac Mansion or Elite, but it influenced later game developers with its courage to be unconventional. The idea of simulating 3D spaces on 8-bit systems was visionary. Developers such as John Carmack later cited Lucasfilm Games as an inspiration – indirectly, The Eidolon contributed to the birth of modern 3D games. The combination of fractal technology with a narrative approach was revolutionary for its time and opened doors for a new type of game design in which immersion and technology went hand in hand.

The game also has cult status among fans. In retrospect, it is often referred to as an “underrated masterpiece” – mainly because of its atmosphere and technical sophistication. Forums and retro gaming communities are full of discussions about strategies, speedruns, and fan projects. Some fans have even designed unofficial sequels or speculatively reconstructed alternative endings. There have even been attempts to remaster the game with modern technology or recreate the engine in order to make its fascination accessible to a new audience. These projects testify to the enduring interest and inspirational power of the game.

Some modern game developers and indie studios refer to The Eidolon as a source of early inspiration in interviews. The mixture of exploration, resource control, and narrative suggestion in particular continues to have an impact today. Games such as Subnautica, Darkest Dungeon, and Return of the Obra Dinn show influences that rely on similar concepts in terms of theme or atmosphere. It seems that The Eidolon, with its quiet, almost forgotten legacy, has left a silent but lasting mark on the DNA of modern game development.

Conclusion

The Eidolon is a game that was ahead of its time – visually impressive, atmospherically dense, and technically innovative. Even if it didn’t appeal to everyone’s taste in terms of gameplay, it marks an important point in the history of video games: the attempt to create something truly immersive with limited resources. It was a pioneer in the way games could combine narrative, aesthetics, and gameplay mechanics – long before these terms became commonplace in the industry. The courage to venture off the beaten path made The Eidolon a pioneer of its time.

For retro gamers and tech nostalgics, The Eidolon is a fascinating excursion into the early days of digital storytelling – and proof of how far you can go with imagination, courage, and a few kilobytes of RAM. It shows that creativity in game development is not tied to technical capabilities, but to the willingness to break new ground. In an era where gaming is increasingly dominated by hyper-realistic graphics and gigantic production budgets, The Eidolon reminds us that atmosphere, ideas, and a willingness to experiment can be just as powerful drivers of playful fascination. Those lucky enough to play a working C64 version today can experience a piece of interactive gaming history – a journey back to the roots, where technology and imagination come together in perfect symbiosis.

Kommentar verfassen :