The year is 1999, and the nations of the earth have declared a world-wide peace plan.

Unfortunately, a council of military commanders has unleased battalions of

automated weapons into the countryside.

These aerial missiles, flying saucers, tanks, and supertanks will turn

the world into lifeless landscape unless you stop them!

A glimpse into the future of video games

When Atari released the arcade game “Battlezone” in 1980, it revolutionized the perception and technical understanding of video games. While most arcade machines of the time featured colorful, two-dimensional playing fields, “Battlezone” broke radically with tradition. With its striking vector graphics and first-person perspective, it catapulted players into a world that had previously only existed in the imagination – a three-dimensional combat zone full of geometric tanks and futuristic threats.

The game quickly became a symbol of technological innovation and creative risk-taking in early video game history. Queues formed in arcades because everyone wanted to “look through the periscope” at least once. With Battlezone, Atari succeeded in creating not just a game, but an experience that allowed players to immerse themselves completely in a digital environment – a taste of virtual reality long before the term existed.

Gameplay

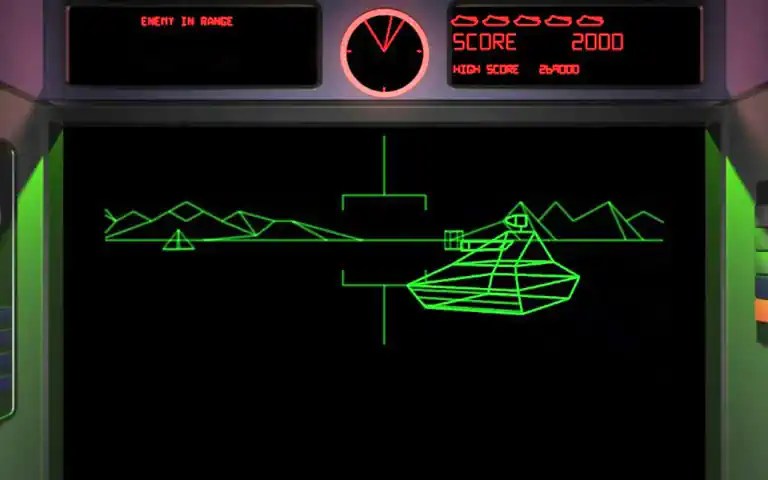

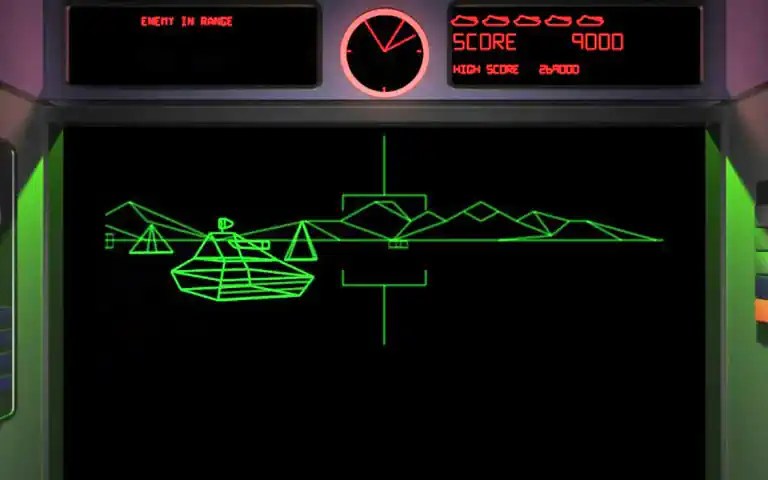

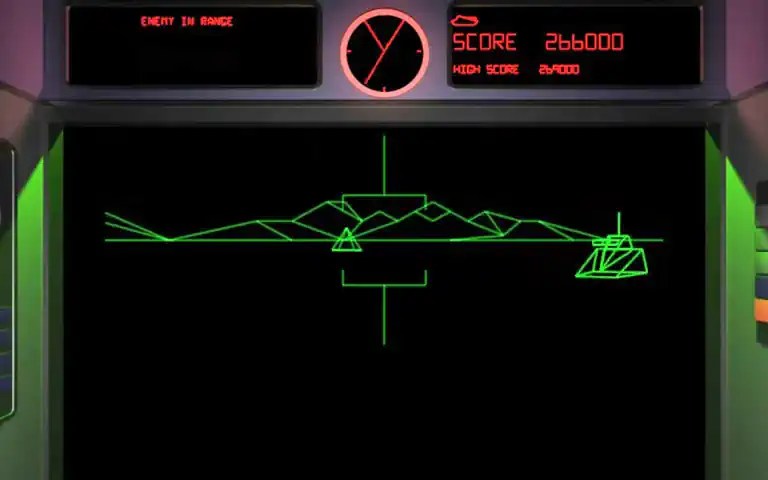

In Battlezone, the player controls a futuristic tank on an open, barren battlefield consisting only of simple lines. This virtual terrain looks like an abstract, digitized interpretation of a post-apocalyptic war landscape – empty, cold, and endless. The goal is simple but captivating: enemy tanks, flying missiles, and occasional UFOs must be destroyed to earn points and survive as long as possible. This creates a mixture of strategic thinking, spatial orientation, and reflexive action that keeps the player in constant suspense. Every shot feels like a small triumph, every hit like a personal setback.

The game uses a first-person view, represented by a green wireframe model of the environment. This minimalist representation nevertheless conveyed an astonishing spatial depth and created a kind of visual “simulation” of a real 3D space long before polygonal graphics were widespread. Obstacles, enemy vehicles, and the horizon were drawn using geometric lines, and the player’s eye had to learn to recognize depth and movement in these line spaces. This principle made “Battlezone” a game that required both imagination and responsiveness.

Two joysticks simulate the movement mechanics of a real tank and contribute greatly to the immersive feeling:

- Both levers forward = forward movement

- One forward = turn forward

- One forward, One backward = rotate

- One backward = turn reverse

- Both back = reverse

These controls made you feel more like a real vehicle driver than a typical arcade player just pressing buttons. The game forced you to coordinate your movements, plan ahead, and think ahead. One careless maneuver could easily lead to you being caught in the line of fire. This made every round an exciting balancing act between attack and defense.

The stylized radar at the top of the screen displays enemy units and becomes one of the player’s most important tools. It not only provides orientation, but also requires interpretation – the player must constantly weigh up which enemies pose an immediate threat and when it makes sense to retreat. The combination of limited visibility, minimalist graphics, and constant pressure creates an intense feeling of isolation and tension. On the empty, linear battlefield, every enemy feels like a fight for survival, every kill like a moment of relief in an otherwise hostile, silent world. This interplay of calm, anticipation, and sudden action made Battlezone a unique blend of tactics, reaction gameplay, and psychological tension.

Technology

Technically, Battlezone was far ahead of its time. The game used a vector graphics engine that drew lines directly on the screen instead of calculating them from pixels. This process enabled sharp, crisp lines and a refresh rate that ensured smooth movement. This created an illusion of depth and space that hardly anyone would have thought possible in the early 1980s. In addition, the system allowed for remarkable precision in the representation of geometric objects. While many competitors were still struggling with flickering pixels, Atari used this technology to create a visual experience that almost resembled a digital hologram. The line construction was not only a stylistic device, but also a necessity—it enabled complex movements with minimal computing power.

The game ran on a specially adapted Atari hardware platform that was optimized specifically for processing vector data. This hardware consisted of a combination of processor, memory, and dedicated graphics chips that worked synchronously to display the lines in real time. The glowing green monochrome display was part of the aesthetic concept: cool, technical, and almost military. Some versions even used slightly varying shades or filters to create a sense of depth. The sound was equally minimalistic but effective—dull explosions, metallic hits, and electronic whistles underscored the sterile atmosphere of the virtual battlefield. This acoustic design greatly enhanced the visual impact, as each signal was precisely synchronized with the image movements.

The arcade cabinet itself contributed significantly to the immersion. It featured a periscope-like viewing window that forced players to look directly into it, blocking out ambient noise. This created a tunnel vision effect that gave the feeling of actually sitting inside a futuristic vehicle. Many players described feeling like they were “looking into another world.” The design of the machine was deliberately ergonomic—the arrangement of the control levers, the position of the monitor, and the height of the viewing aperture conveyed a half-real, half-virtual driving experience. Some arcade visitors reported that they still felt “phantom movements” after playing – an early indication of how strongly digital spaces can influence perception. This physical connection between machine and human made “Battlezone” a precursor to later virtual reality systems.

Trivial

- The rare UFO flying over the battlefield is difficult to hit but scores a lot of points. It has no direct threatening function but serves as a reward for attentive players. Some players reported that they tried to deliberately keep the UFO alive in order to study its flight paths – an early example of emergent gameplay.

- The famous “Volcano” mountain in the background has no gameplay function, but was designed as a visual orientation aid – an example of how minimalist design can still create atmosphere. It also served as a testing ground for the vector graphics engine: developers used the mountain to test contour lines, shading, and perspective distortions, which were later reused in other games.

- Lead developer Ed Rotberg had to convince Atari that the complex hardware was worth the effort – a risk that would pay off. He worked in a small, highly specialized team that often stayed in the lab at night to optimize the line calculation and stability of the system. This dedication resulted in exceptional technical quality.

- There were internal discussions about whether the game was too “military,” but its success quickly won over the critics. Some designers feared that the depiction of tank battles might be controversial, but the audience interpreted the game more as a science fiction experience than a realistic war simulator. Atari therefore cleverly marketed it as a futuristic “tank adventure” rather than a combat game.

- Battlezone is considered one of the first games to use a radar system as a central game element. This radar served not only as an aid, but also as a style-defining element: the circular interface inspired many later games – from Elite and Defender to modern titles with mini-map mechanics. It marked the beginning of a new era of user interfaces that combined tactical overview and immersion.

Military version

The success of Battlezone did not go unnoticed outside the arcades. In 1981, the US Army approached Atari to develop a more realistic version for training purposes – the legendary Bradley Trainer. This variant was designed to help soldiers of the Bradley Fighting Vehicle familiarize themselves with tactical situations and train basic navigation and targeting exercises. The move was unusual for both sides: for the military, it was an experiment in using modern entertainment technology as a training aid, while Atari was venturing into completely new territory.

The “Bradley Trainer” differed significantly from the arcade original: the controls were expanded, the radar was made more precise, and the enemies were programmed to be more intelligent. In addition, players could now simulate different types of tanks, terrain types, and weapon modes. There were terrain profiles, various training missions, weather settings, and even friend-or-foe identification, which further enhanced the realism. Atari worked with real military advisors to tailor the game to the needs of the army and implemented feedback from test pilots and instructors into the code. Only a few prototypes were produced, and they were long considered lost. Today, one is housed in the National Museum of American History, another is privately owned, and there are rumors of a third, unfinished prototype that included additional scenarios.

This collaboration between a game studio and the military was an early example of the convergence of entertainment technology and real-world training—a theme that would become increasingly relevant in the coming decades with flight simulators, VR systems, and even e-learning platforms. Today, the Bradley Trainer is considered the precursor to the military virtual reality training environments that became standard in the 1990s. It showed that video games could be much more than mere entertainment: they could impart knowledge, train responses, and finally blur the line between game and simulation.

Criticism at the time

Contemporary critics were enthusiastic and amazed by the visual and technical sophistication of Battlezone. Magazines such as Electronic Games called it “the most realistic video game ever,” and trade publications such as Computer and Video Games praised the precision and “immense sense of depth” created by the vector graphics. Some reviewers went so far as to describe the game as a form of digital artwork – a technical triumph that captured the spirit of the machine age. Players described the feeling of “really sitting in a tank” – a sensation that no game had ever evoked before. Many reported an eerie immersion in an empty, mechanical world where sound, movement, and visual reduction merged into an intense psychological experience.

Some critics complained about the high level of difficulty, but that was precisely what made it so appealing. Battlezone rewarded patience, precision, and strategic thinking, while at the same time demanding a certain amount of mental stamina. Some players found the learning curve frustrating, but others saw it as a sign of depth and realism. Particularly impressive was the fact that the game character – the tank – had no visible form, but could only be experienced through instruments, radar, and perspective. This abstraction gave the game an almost philosophical touch: the player himself is the machine, a symbol of the fusion of man and technology in a virtual environment. In later retrospectives, this concept was described as a precursor to cybernetic game theory, in which humans not only operate the machine, but become an integral part of its system.

In arcades, Battlezone quickly became a crowd-puller. It was expensive but popular, and was often advertised as “the future of video games.” For many, it was their first encounter with a form of virtuality that went beyond mere reflex games. Some operators reported that players stood at the machines for hours, fascinated by the illusion of depth and movement. The audience ranged from teenagers to engineers and technology enthusiasts who saw the game as proof that video games could be more than just a pastime – they were a glimpse into the future of digital perception.

Cultural influence

The influence of Battlezone on the video game world can hardly be overestimated. It was one of the pioneers of 3D gaming and inspired countless later titles – from Elite (1984), which also used vector graphics, to Wolfenstein 3D (1992) and Doom (1993), which perfected the first-person perspective. Modern tank and combat simulators also owe their basic concept to the game. However, its significance extends far beyond the genre: Battlezone laid the foundation for the understanding of digital spaces in which the player becomes part of the world, thus influencing the long-term development of immersive environments in virtual and augmented reality applications.

Furthermore, Battlezone shaped the aesthetic self-image of digital culture. Its minimalist, geometric forms became a visual symbol of early computer worlds and inspired artists, designers, and filmmakers alike. In films such as Tron (1982), The Last Starfighter (1984) and Ready Player One (2018) contain clear references to the game’s gameplay and vector graphics. Similar line art also appeared in music videos and advertising campaigns of the 1980s, deliberately referencing the style of Battlezone to symbolize technological modernity. Atari itself released several new editions, including Battlezone 2000, Battlezone: Redux, and Battlezone VR, which modernized the concept for new generations of players and, in some cases, introduced online multiplayer modes.

Even artists and designers referenced the aesthetics of Battlezone. The combination of military realism and abstract representation served as a template for numerous experiments in media art, architectural visualization, and interface design. Universities even used the graphic philosophy of Battlezone in courses to explore spatial perception and minimalist design. Battlezone was thus not only a technical masterpiece, but also a cultural artifact that redefined the dialogue between humans, machines, and space, and continues to have an impact on digital art and gaming history to this day.

Conclusion

Battlezone was more than just an arcade game—it was a milestone in computer game history and a harbinger of the 3D age. With its innovative technology, immersive perspective, and visionary combination of gameplay and simulation, it set standards that are still felt today. It showed that an arcade machine did not have to be based solely on reaction speed, but also on strategic thinking, spatial orientation, and atmospheric immersion. Players did not simply become observers, but active participants in an artificial world that challenged them emotionally and intellectually.

The game proved that video games could be more than just entertainment: they could create illusions of reality, trigger emotions, and even serve as training tools. Battlezone opened up a new dimension of interactivity in which technology and human perception merged. Its minimalist presentation forced the player’s brain to fill in gaps and construct meaning—a feature that is now considered one of the key elements of immersive media. More than four decades later, Battlezone is still considered a prime example of how creative engineering and design vision can come together to create something truly new—a window into a digital future that was just beginning at the time. It remains a symbol of the moment when technology became art and the beginning of an era in which video games transcended the boundaries between simulation, narrative, and experience.

Kommentar verfassen :